Trump Accounts as an Opportunity to Reduce Exponential Growth Bias and Improve Financial Security

The new children's savings accounts offer financial education opportunities -- but choice architecture is likely to have a bigger influence on their ability to deliver broad-based wealth accumulation.

The Trump Accounts program, created through the One Big Beautiful Bill Act of 2025, provides each U.S. child born between 2025 and 2028 with a $1,000 government contribution invested in low-cost stock index funds. Families with children can contribute up to $5,000 annually, with the funds growing tax-deferred until the child turns 18, at which point they could be transitioned into an individual retirement account (IRA).

While the program generated headlines for its promised wealth accumulation, it also presents a new educational opportunity around saving and investing. Recognizing this, the U.S. Treasury’s Financial Literacy and Education Commission recently released a Request for Information to help review its strategy—in particular, to inform how financial education providers can “best use investment vehicles, like Trump Accounts, to teach children how to save, invest, and achieve financial security.” We describe how these accounts could help millions of Americans better understand exponential growth and improve their own retirement saving behavior, addressing a widespread cognitive bias associated with lower levels of retirement savings. In addition, we point out the limitations of financial education and why the choice architecture that accompanies Trump Accounts is poised to have a large influence on their success as vehicles of wealth accumulation. Thus, financial education and the ways in which choices are offered can complement one another towards the goal of broad-based wealth accumulation.

Exponential growth bias is prevalent and consequential in wealth accumulation

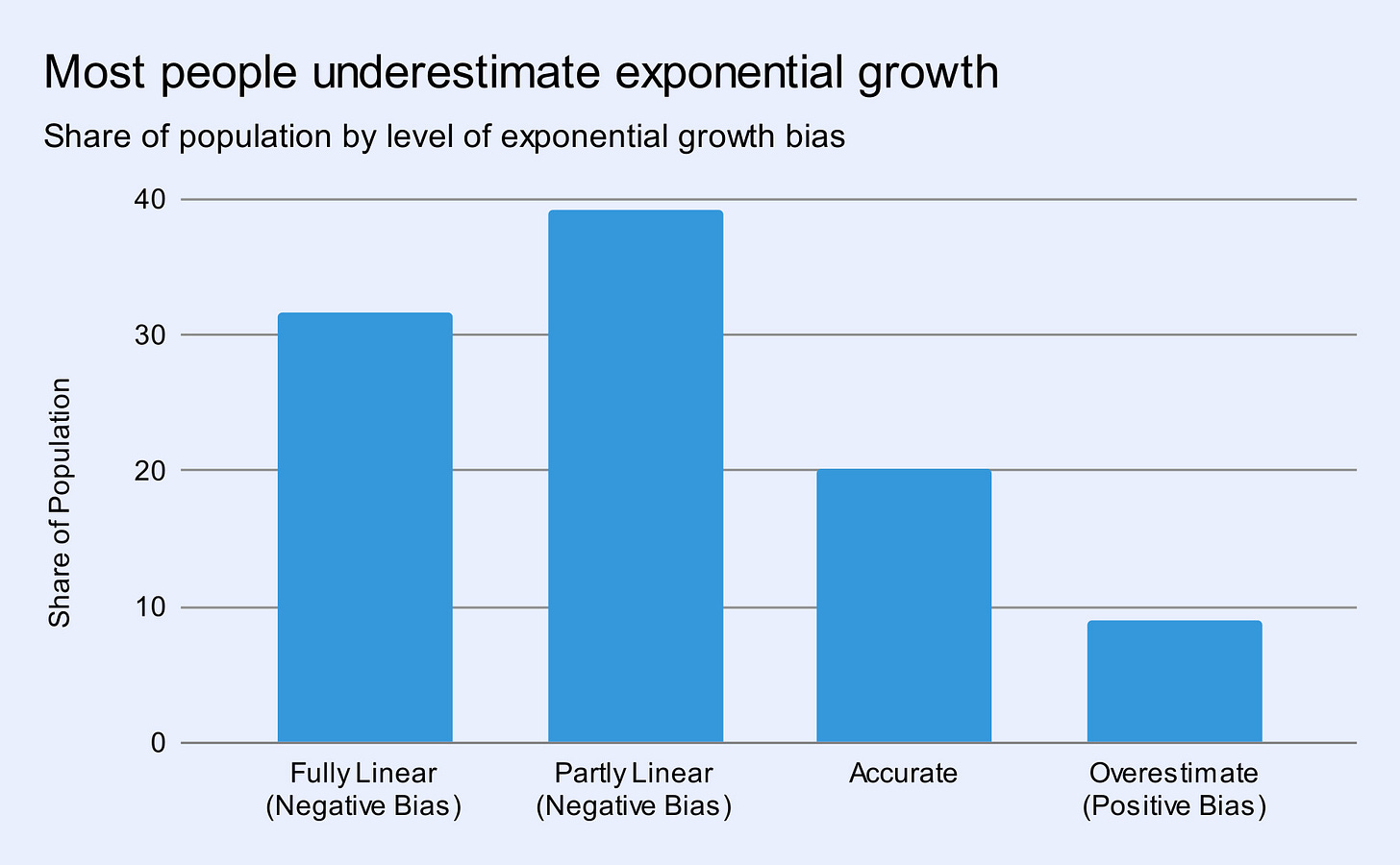

Exponential growth bias (EGB) is the tendency to misestimate how quantities grow when they compound over time. People with negative exponential growth bias perceive compound growth as if it were closer to linear growth, where their savings increase by a fixed dollar amount each period rather than accelerating as returns compound on previous returns. This bias is pervasive: research shows that approximately 70 percent of the U.S. population exhibits negative exponential growth bias, with almost a third of individuals perceiving compound growth to be linear (Levy and Tasoff, 2016; Goda et al., 2019).

People who exhibit negative exponential growth bias perceive that returns to investing will be smaller than they actually are, particularly over longer time horizons. While this bias could, in theory, lead to either undersaving or oversaving, research by our team has found that it is strongly associated with lower levels of retirement savings, even after controlling for cognitive ability, financial literacy, income, education, age, and other demographic factors (Goda et al., 2019).1 Specifically, moving from a typical level of bias to a more severe level of bias is associated with substantially lower average retirement account balances at age 65. Under an assumption that the relationship we estimate is causal, eliminating exponential growth bias across the population could increase retirement savings by 12% to 70%, depending on modeling assumptions.

How Trump Accounts could serve as an educational tool

Trump Accounts present an opportunity to help people overcome exponential growth bias through direct, personal experience with compound growth given the initial government contribution starts at birth, initiating experience with compound growth in a child’s (and family’s) formative years. Unlike abstract educational programs about retirement saving or textbook examples, these accounts involve real money growing over time in accounts that belong to the user’s child or family member. This creates natural opportunities for families to engage with compound growth concepts repeatedly. These lessons may translate to knowledge that young people can apply during their subsequent working and wealth-building years.

The Trump administration has offered a website that provides information about how the accounts work and includes projected wealth accumulation in those accounts by certain ages under one set of assumptions, claiming that accounts would accumulate to more than $200,000 by age 55 with no more than a $1,000 contribution at birth. Similar projections have also been described in a report by the Council of Economic Advisors. As discussed extensively by Alan Viard, however, the “administration’s projections greatly overstate the accounts’ likely payoff” because they do not adjust for inflation and taxes and they rely on extremely optimistic assumptions regarding future stock returns. Taking inflation into account, conservative estimates of taxes that would be owed, and using rates of return that are at the top end of six major investment firms’ forecasts, Viard estimates that the $1,000 investment would result in after-tax buying power of $8,000 in today’s dollars.

Providing projections based on a particular, inflexible set of assumptions that also convey certainty is a limitation to financial learning. To further the educational opportunity, the administration could instead create a tool that allows people to enter rates of return, additional contributions, and other details. That would allow families to determine how funding accounts for children today could accumulate into the future.

The results of integrating financial education in a real-world setting has some promise. Our research shows that providing people with personalized retirement income projections significantly increases retirement contributions (Goda et al., 2014). In a field experiment with university employees, those who received projections showing how current savings would translate into retirement income contributed approximately $85 more annually than the control group. Among those who made changes to their contributions, the increase averaged $1,150 annually.

Further, the Setting Every Community Up for Retirement Enhancement (SECURE) Act, signed in December 2019, included provisions to require defined contribution plans like 401(k)s to provide lifetime income disclosures to their participants. In 2020, the Department of Labor described the requirements in regulations that took effect in September 2021, which include the types of projections required, actuarial and interest rate assumptions, and model language.

Trump Accounts would not be subject to these requirements; however, these requirements and recent research can offer insights into how to integrate projections and tools into the rollout of Trump Accounts to help consumers make contributions that better fit their goals and constraints. We highlight some opportunities here.

First, record keepers should use both personalized mailings and online calculators to serve complimentary purposes. Account statements provide a periodic snapshot of the account balance, and offer an opportunity to provide projections of accumulated balances under a limited number of assumptions. Online calculators can allow account holders the ability to adjust expected rates of return, adjust for inflation, estimate taxes and explore how making additional contributions impact the projections across different time horizons. However, evidence from a randomized control trial our team conducted suggests that those who access online tools are more likely to already be making high contributions and have higher levels of financial knowledge, thus limiting their reach (Goda et al., 2023).

Second, informational materials should account for the potential anchoring to assumptions. Our first study of non-adjustable mailers showed that the effect of projections on employee contributions varied by assumptions on retirement age and the scenarios presented (Goda et al., 2014). However, in a later experiment with an adjustable online calculator, initial assumptions did not affect savings (Goda et al., 2023). Thus, non-adjustable assumptions may anchor individuals to certain projections, but these anchoring effects can be mitigated by allowing users to change assumptions.

Finally, financial information should be provided at moments when individuals are making relevant financial decisions. Research shows that this “just in time” information tends to be significantly more effective. A meta-analysis by Fernandes, Lynch, and Netemeyer (2014) found that even large interventions with many hours of instruction have negligible effects on behavior 20 months or more from the time of intervention, suggesting that financial knowledge, like other forms of education, decays over time when not immediately applied. Kaiser and Menkhoff (2017) in their meta-analysis of 126 impact evaluation studies found that intervention success depends crucially on offering financial education at a “teachable moment.” The effectiveness of just-in-time education stems from its ability to overcome the temporal gap between learning and application that undermines conventional financial literacy programs. When individuals receive targeted information precisely when facing decisions about mortgages, debt management, or retirement planning, they can immediately incorporate that knowledge into their choices, enhancing both comprehension and retention while the motivation to learn and apply new concepts remains high. These findings suggest that providing information during a time when people are actively making financial decisions—such as when they are filing their taxes or enrolling in benefits—can increase the likelihood that the information is acted upon.

Research on retirement savings offers more lessons for Trump Accounts beyond education

While the Trump Accounts offer opportunities for education, the bulk of the evidence in the retirement savings literature suggests that it is difficult to move the needle on savings decisions solely through informational interventions. Financial literacy and counseling can improve knowledge, but the impacts on actual saving behavior are typically modest and uneven—especially when programs are delivered as one-off modules, are optional, or require people to translate abstract information into concrete actions amid competing demands (Hastings, Madrian, & Skimmyhorn 2013; Fernandes, Lynch, & Netemeyer 2014; Lusardi & Mitchell 2014). This gap between knowing and doing is why retirement policy over the last two decades has increasingly focused on how decisions are structured, not just what people are told.

In that context, the key takeaway for Trump Accounts is that “choice architecture”—the design of the choice environment—often dominates education. Automatic enrollment has repeatedly been shown to produce large, immediate increases in participation relative to opt-in systems because inertia and procrastination are powerful (Madrian & Shea 2001; Choi et al. 2004). Defaults also shape how much people save and how they invest: many participants accept default contribution rates and default asset allocations even when those defaults are not tailored to their circumstances (Choi et al. 2004; Beshears et al. 2009). If Trump Accounts are meant to build assets at scale, the most consequential design decisions will be the default enrollment mechanism, the way additional contributions are made (including whether contributions can “step up” over time), and the default investment option—because these features will determine outcomes for the many households that do not make active choices.

The retirement literature also suggests that simplifying the decision process and reducing “hassle costs” can amplify the power of defaults. When the action required to participate is small (or eliminated entirely), participation rises; when the process is complex, take-up falls, particularly among lower-income and less financially confident households (Madrian & Shea 2001; Beshears et al. 2009). For Trump Accounts, that would imply design choices that include making enrollment automatic, allowing contributions to be set up seamlessly through payroll withholding and tax refunds, keep the menu of choices limited and standardized, and using a prudent, low-cost investment fund as the default (Benartzi & Thaler 2007; Beshears et al. 2009).

Finally, the evidence points to complementary “autopilot” features that could materially strengthen Trump Accounts if the goal is persistent saving rather than one-time account opening. Automatic contribution escalation—popularized in retirement plans—can increase saving rates over time while minimizing perceived pain at any single moment (Thaler & Benartzi 2004). The transition into public pre-k or kindergarten can open up substantial space in family budgets previously stretched by child care expenses. Thus, allowing families to pre-commit to increase their savings at that transition might be fruitful. Portability and continuity matter, too: when saving is tied to a job, leakage and interruptions can erode balances; when saving mechanisms persist across job changes, balances tend to grow more reliably (Beshears et al. 2009). Translating these lessons to Trump Accounts means ensuring that accounts follow individuals across employers and life transitions, and reducing the number of required active steps—especially for households most likely to benefit from sustained asset accumulation.

Conclusion

Trump Accounts represent an opportunity for experiential financial education at a large scale. If designed thoughtfully, with realistic projection tools that account for investment returns, taxes, inflation, and various contribution scenarios delivered at the right time, these accounts could help millions of Americans develop a more accurate understanding of compound growth. This understanding could lead to better decision-making regarding retirement savings into the future.

However, realizing this potential requires deliberate policy choices. Providers must build user-friendly tools with realistic assumptions. Regulators should ensure that marketing materials present balanced scenarios and allow opportunities for exploration among a broad set of individuals, not just those who have higher levels of financial capability to begin with. And the design of the choice architecture will arguably have an even larger impact on the eventual wealth accumulated in these accounts into the future. For Trump Accounts to provide broad-based opportunities for wealth accumulation over the life cycle, policymakers need to take a multi-pronged evidence-based approach.

References

Benartzi, S., & Thaler, R. H. (2007). Heuristics and biases in retirement savings behavior. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 21(3), 81–104.

Beshears, J., Choi, J. J., Laibson, D., & Madrian, B. C. (2009). The importance of default options for retirement saving outcomes: Evidence from the United States. In Social Security Policy in a Changing Environment (University of Chicago Press volume).

Choi, J. J., Laibson, D., Madrian, B. C., & Metrick, A. (2004). For better or for worse: Default effects and 401(k) savings behavior. In D. A. Wise (Ed.), Perspectives on the Economics of Aging (University of Chicago Press volume).

Fernandes, D., Lynch, J. G., Jr., & Netemeyer, R. G. (2014). Financial literacy, financial education, and downstream financial behaviors. Management Science, 60(8), 1861–1883.

Goda, G. S., Manchester, C. F., & Sojourner, A. J. (2014). What will my account really be worth? Experimental evidence on how retirement income projections affect saving. Journal of Public Economics, 119, 80–92.

Goda, G. S., Levy, M. R., Manchester, C. F., Sojourner, A., & Tasoff, J. (2019). Predicting retirement savings using survey measures of exponential-growth bias and present bias. Economic Inquiry, 57(3), 1636-1658.

Goda, G. S., Levy, M. R., Manchester, C. F., Sojourner, A., Tasoff, J., & Xiao, J. (2023). Are retirement planning tools substitutes or complements to financial capability?. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 214, 561-573.

Hastings, J. S., Madrian, B. C., & Skimmyhorn, W. L. (2013). Financial literacy, financial education, and economic outcomes. Annual Review of Economics, 5, 347–373.

Kaiser, T., & Menkhoff, L. (2017). Does financial education impact financial literacy and financial behavior, and if so, when? The World Bank Economic Review, 31(3), 611–630.

Levy, M. R., & Tasoff, J. (2016). Exponential-growth bias and lifecycle consumption. Journal of the European Economic Association, 14(3), 545-583.

Lusardi, A., & Mitchell, O. S. (2014). The economic importance of financial literacy: Theory and evidence. Journal of Economic Literature, 52(1), 5–44.

Madrian, B. C., & Shea, D. F. (2001). The power of suggestion: Inertia in 401(k) participation and savings behavior. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 116(4), 1149–1187.

Thaler, R. H., & Benartzi, S. (2004). Save More Tomorrow™: Using behavioral economics to increase employee saving. Journal of Political Economy, 112(S1), S164–S187.

Viard, A. D. (2026). Trump Administration presents grossly exaggerated projections of Trump Accounts’ payoffs. AEIdeas. https://www.aei.org/economics/trump-administration-presents-grossly-exaggerated-projections-of-trump-accounts-payoffs/

For instance, if one misperceives the return to saving to be low, they may prefer to overconsume more today. On the other hand, low returns to saving might incentivize people to save more if they are trying to achieve a given level of retirement savings. Those who exhibit exponential growth bias may also take on too much debt because they underestimate the long-term cost of borrowing at compound interest rates.