Tax Credits and the Safety Net: Proven Tools That Could Do Even More

The EITC and CTC effectively deliver over $180 billion in aid annually and could still be improved

Each year, tens of millions of American families receive support through two important tax credits: the Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC) and the Child Tax Credit (CTC). Together, they deliver over $180 billion annually to working households—more than the federal government spends on food assistance, housing aid, and cash welfare combined. The EITC and CTC form the core of the country’s work- and family-support policy—rewarding employment, supplementing earnings, and helping parents meet the costs of raising children.

While the EITC and CTC share a common goal of improving family well-being and operate in similar ways, they differ in who they primarily benefit. The EITC is a fully refundable credit targeted toward low-income households, boosting after-tax earnings and lifting millions out of poverty each year. The CTC, by contrast, is a partially refundable credit that extends high up the income distribution, helping middle- and upper-middle-income families, but only modestly supporting those with the lowest incomes.

Understanding these two credits is key to understanding America’s social safety net and the ongoing debate over how best to support working families. The goal of this post is to describe three aspects of these two tax credits: (1) their current design and historical development, (2) research evidence on their effects on families, and (3) ways they could be improved.

The EITC: Increasingly Important for Low-Income Families Since 1975

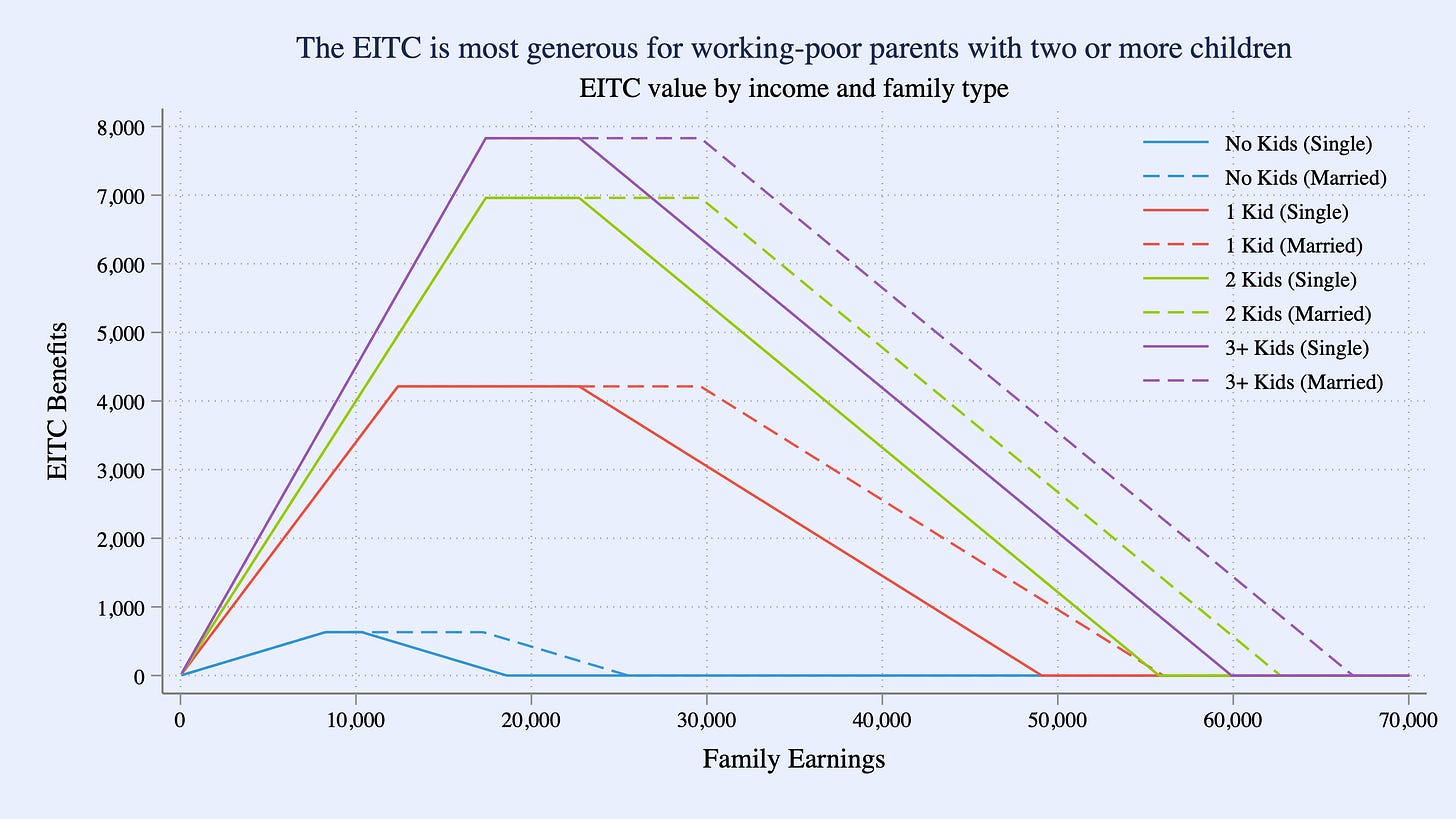

The EITC is a refundable tax credit that reaches about 25 million low- and moderate-income households and delivers roughly $60 billion in benefits each year. Designed to reward work and support families, the credit increases with earnings up to a threshold—rising by 34 cents per dollar for families with one child, 40 cents for those with two children, and 45 cents for families with three or more children—before plateauing for moderate-income households and gradually phasing out. Maximum benefits are about $8,000 for families with three or more children, $7,000 for those with two children, and $4,000 for those with one child, but only about $600 for those without qualifying children. Figure 1 illustrates the 2025 EITC and is based on IRS data. Because it is fully refundable, the EITC provides meaningful income support even to families with little or no tax liability—often representing a quarter or more of their annual income.

The EITC was created in 1975 as a wage subsidy for low-income families intended to “make work pay” and offset payroll taxes. Congress modestly expanded the credit several times over the next decade, before the largest expansion in the 1990s, which created separate benefit schedules for workers with no children, one child, and two or more children. Maximum credits for families with two or more children roughly tripled in real terms, and total program costs rose from about $15 billion to nearly $60 billion (in 2025 dollars). Later reforms in the 2000s and 2010s added modest marriage-penalty relief and a higher credit rate for families with three or more children.

Building on the federal model, 30 states and the District of Columbia offer their own EITCs, typically as a percentage match of the federal benefit. Programs vary widely in details and generosity—ranging from small matches of around 5–10% to more ambitious designs in places like Maryland, New Jersey, and the District of Columbia, which have matches of 40–70%. These state credits collectively deliver about $7–8 billion annually and have become an important complement to the federal EITC.

The CTC: A Middle-Income Credit Since 1997

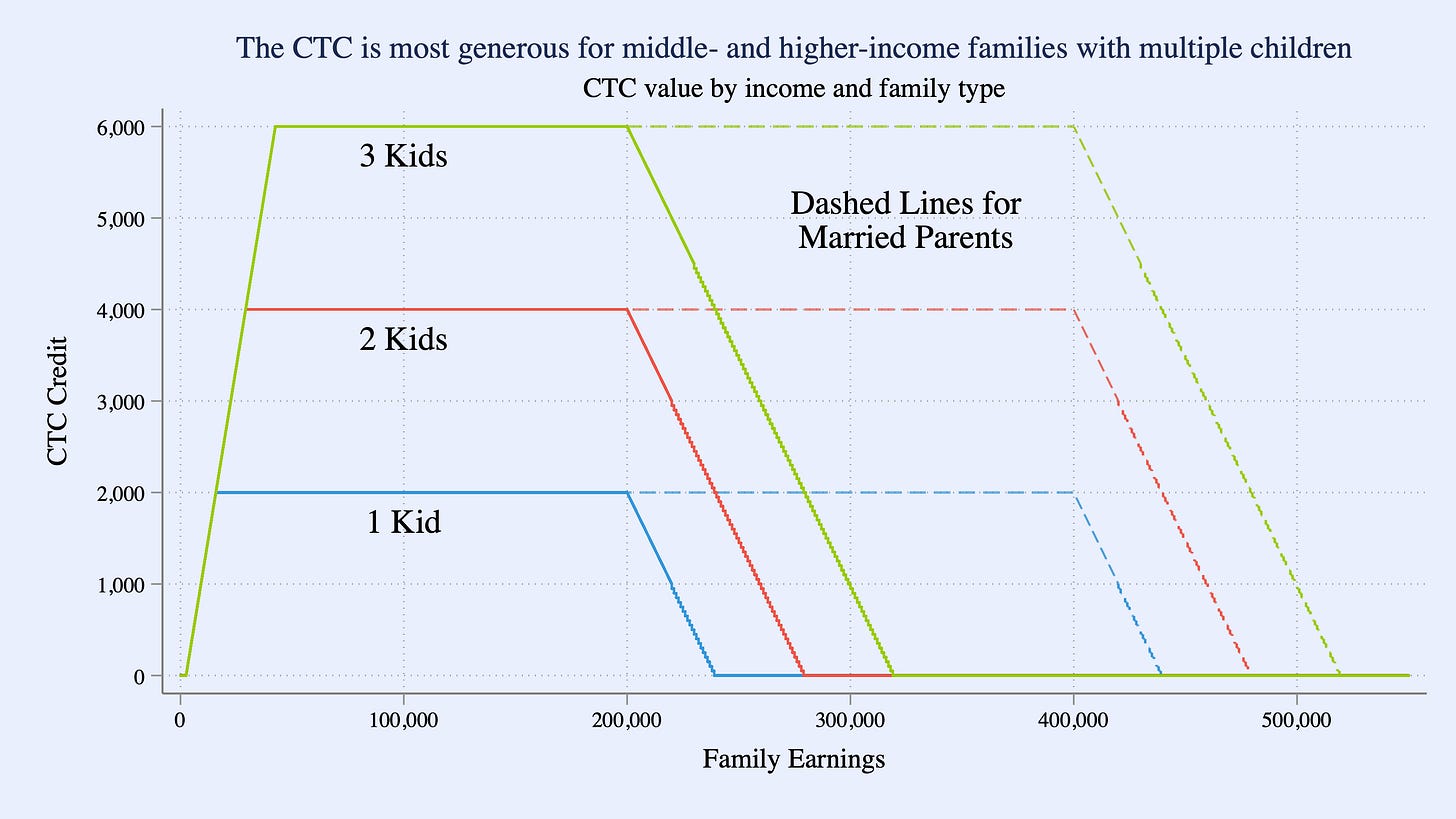

The CTC is a major federal program that helps working families offset the cost of raising children, reaching roughly 40 million households and delivering about $120 billion in benefits each year. Like the EITC, it varies by household income, filing status, and number of qualifying children. Unlike the EITC, benefits extend much further up the income distribution. Figure 2 illustrates the 2025 CTC and is based on IRS data. The maximum credit in 2025 was $2,000 per child, with up to $1,700 refundable. Unlike the EITC, however, CTC benefits phase in more slowly—at 15 cents per dollar earned above $2,500.

Created in 1997, the CTC began as a nonrefundable tax credit aimed at middle-income families, offering up to $400 per child. Over the next two decades, the credit steadily expanded to reach more families and increase refundability. The 2017 Tax Cuts and Jobs Act doubled the maximum CTC to $2,000 per child and expanded eligibility to higher-income families, while also creating a smaller $500 Credit for Other Dependents for older children and non-child dependents.1 The 2021 American Rescue Plan briefly transformed the CTC into a fully refundable monthly child allowance—$3,600 per child under six and $3,000 for older children. After that temporary expansion expired, the credit reverted to its prior structure and a maximum of $2,000 per child. A small 2025 expansion raised the maximum benefit to $2,200 per child, with $1,700 refundable.

A growing number of states have established their own CTC to supplement the federal benefit. As of 2025, more than a dozen states—including California, New York, Minnesota, Utah, Colorado, Vermont, and Oklahoma—offer refundable or partially refundable CTCs, typically ranging from a few hundred dollars to over $1,000 per child. These programs vary in eligibility and structure but generally target low- and middle-income families. Collectively, state CTCs provide $3–4 billion each year in additional support, strengthening the overall safety net for families in states offering CTCs.

Who Receives These Credits?

Unlike nonrefundable tax credits, which only reduce taxes owed, refundable credits can exceed a family’s tax liability and provide a direct payment. This distinction matters because most families with children owe little or no federal income tax until their earnings exceed roughly $50,000, meaning only refundable credits reach those most in need.

Although both programs support working families, their benefits are distributed very differently across the income spectrum. The EITC is highly progressive—ramping up quickly at low earnings, peaking at modest wages, and phasing out around $50,000. More than 90% of EITC dollars go to families earning under $40,000, about half of them single mothers. The CTC, by contrast, delivers most of its benefits to higher-income families: in 2023, roughly 70% of all CTC dollars went to families earning above $50,000, while those below $30,000 received less than 10%.

Because full CTC benefits extend up to $400,000 for married couples and $200,000 for single filers, simply increasing the maximum credit, as in the 2025 change, is a costly and poorly targeted approach. A family with three children must earn at least $40,000 to access the full refundable amount, while households earning up to $400,000 remain eligible for the maximum credit—meaning children in higher-income families benefit more than the roughly 20 million poorest children in the U.S.

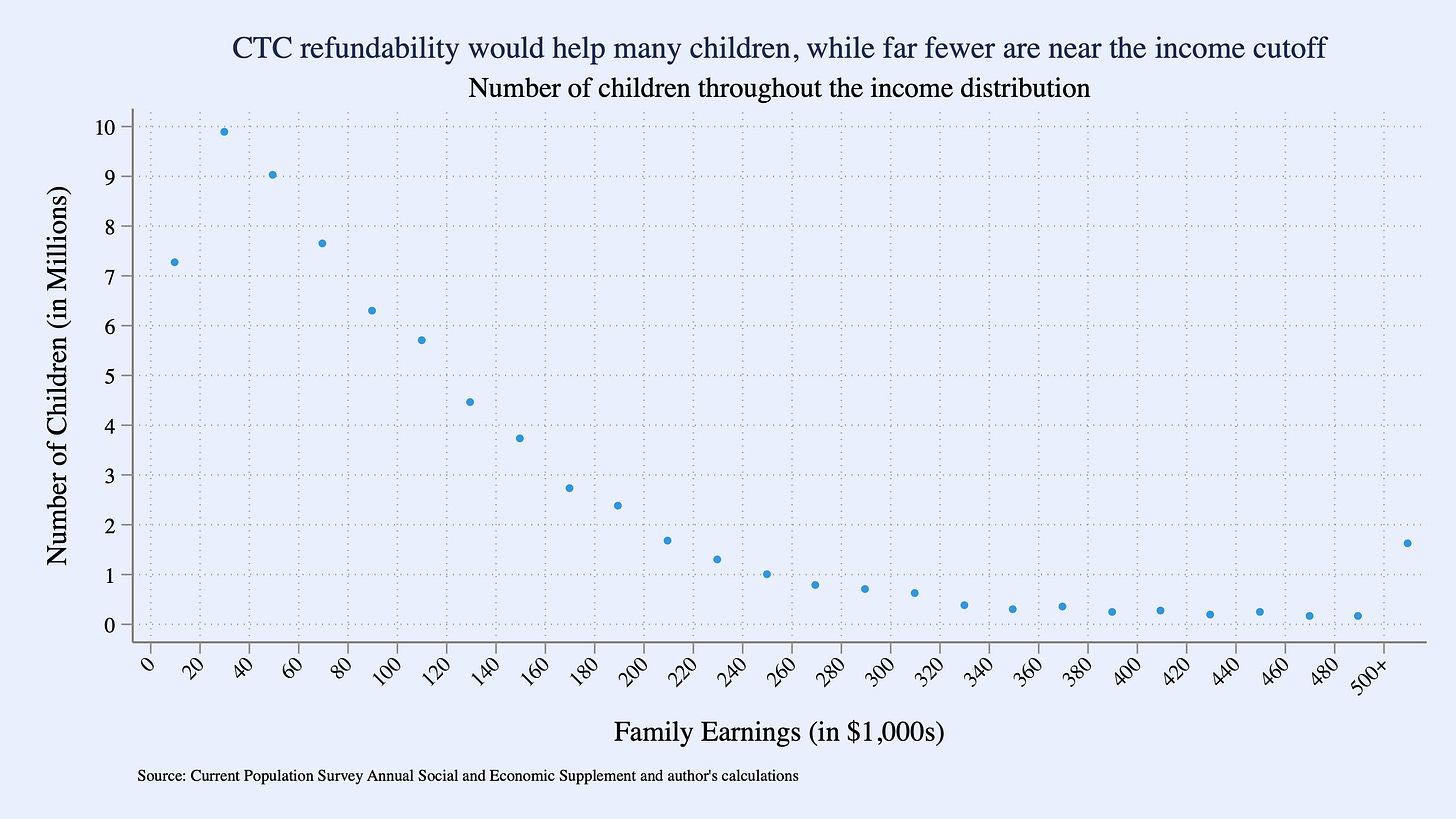

Figure 3 illustrates where children fall across the income distribution. Of the 69 million children under age 18 in the United States, more than 7 million live in families earning below $20,000 a year, and 40 million are in families with incomes under $100,000. In contrast, 10 million children live in households earning above $200,000, including 2.5 million in those above $400,000. These figures show that millions of children grow up in families with very low incomes—and highlight why expanding the refundable portion of the CTC would do far more to reach those most in need.

Research Shows Short- and Long-Run Benefits of Tax Credits for Children

Decades of research show that the EITC is one of the most effective tools for supporting low- and moderate-income families. By increasing take-home pay and the return to work for parents, it substantially boosts employment—especially among single mothers. Major expansions in the 1970s and 1990s led to large gains in labor force participation. Each year, the EITC lifts about 5–6 million people—including roughly 3 million children—above the poverty line and reduces the depth of poverty for millions more.

Beyond its immediate effects on income and work, the EITC improves several additional short- and long-run outcomes. The additional income reduces financial stress, improves maternal physical and mental health, reduces smoking, and helps families move to neighborhoods with greater economic opportunity. For children, larger credits are linked to higher birth weights, better health, stronger school performance, and higher rates of high-school graduation. These benefits persist into adulthood when these children reach their 20s and 30s: they are more likely to attend and graduate from college, work and earn more, experience better health, and have lower rates of mortality. These positive effects operate through both higher parental earnings and the transfer income itself since benefits are evident among children from married families (who do not raise labor supply after EITC expansions) and unmarried families (who do).

Research on the CTC shows smaller effects on families than the EITC, reflecting its slower phase-in and limited refundability. However, the 2021 expansion briefly transformed the CTC into a near-universal child benefit—and the results were striking. Monthly payments sharply reduced food insecurity, material hardship, and financial stress, while improving parents’ mental health and ability to meet basic needs. Most of the benefits paid for food, rent, utilities, debt repayment, and school supplies. Despite concerns about work disincentives, evidence shows little impact on labor-force participation, although it is possible that these effects would have grown over time had the program become permanent. The 2021 expansion cut child poverty nearly in half—demonstrating that child poverty is a policy choice that can largely be reversed through a fully refundable and accessible credit.

Ways to Make These Policies Even Stronger

Despite their proven success, both the EITC and CTC have significant gaps that policymakers could address to strengthen their reach and effectiveness.

EITC improvements. One of the EITC’s main weaknesses is its treatment of workers without qualifying children, who receive less than $600 annually—just a fraction of what families with children receive. Expanding the credit for these workers would meaningfully reduce poverty, particularly among younger adults, and could also help older adults whose children have aged out of eligibility and who therefore experience a de facto wage cut when their EITC benefits disappear.

Under current law, the EITC requires that both the filer and each qualifying child have valid Social Security numbers, making mixed-status immigrant families ineligible even when the children are U.S. citizens. The CTC, by contrast, allows parents to file with an ITIN as long as the child has an SSN. Expanding EITC eligibility to align with the CTC’s rules would extend the credit to an estimated 4.5 million U.S. citizen children who are currently excluded.

Improving take-up and simplifying access is often discussed as a top priority. Nearly one in five eligible families fails to claim the EITC (compared to about 93% for the CTC), leaving billions of dollars unclaimed each year. However, take-up among families with children is closer to 90%, while it is closer to 50% among those without children that are eligible for much less. Many families who do claim the credit rely on paid preparers who capture a share of the very benefits these programs are meant to provide. Policymakers could make filing easier through automatic eligibility checks, prefilled tax forms, and broader access to free, user-friendly filing tools. Instead, Congress ended the IRS Direct File pilot program—a move that will make filing more time-consuming and costly for many low-income families.

The precertification idea considered by Congress in 2025—requiring families to verify EITC eligibility with the IRS before filing their tax return—would have been a serious step backward. In practice, it would operate like a universal audit for low-income families, discouraging many from claiming the credit they are owed. This approach has been tried before—and failed: a 2003 IRS pilot using a similar process caused many eligible families to drop out entirely. Adding new red tape would again deter legitimate claims and delay refunds, weakening a program proven to boost work, reduce poverty, and improve child outcomes.

A concern driving the precertification idea—the EITC’s “improper payment” rate—is often misunderstood. Improper payment rates of 22% to 33% include all payments that differ from what the IRS later determines to be correct, regardless of intent. Most of these discrepancies arise from unintentional eligibility or reporting errors—for example, confusion about which parent can claim a child, how to report part-year income, or whether informal earnings qualify. Estimates based on detailed IRS audit data show that only 7–8% of EITC dollars are linked to intentional misuse, where claimants knowingly provide false information. Overall, roughly 4% involve actual fraud, such as fabricated income or dependents. In short, the vast majority of EITC “errors” reflect good-faith mistakes or claims that still benefit the child’s household, not fraud.

Safety-net programs face a tradeoff between erroneous payments and administrative costs. Together, these determine how much of a program’s spending fails to reach intended beneficiaries. The EITC’s administrative cost is only about 1% of total spending—far lower than many other safety-net programs, including roughly 6% for SNAP and 10% for TANF. As a result, the overwhelming majority of EITC funds go directly to eligible working families.

CTC improvements. The CTC could be restructured to better reach low-income families. Making the credit fully refundable—or phasing it in faster, with higher rates for families with multiple children as in the EITC—would enhance work incentives and channel more assistance to families in need. The cost of CTC expansions and more generous benefits to lower-income families could be offset by lowering the phase-out threshold from its current $400,000 for married couples to $200,000, which would save an estimated $24 billion annually while maintaining broad access for families in need.

It is also important to consider age eligibility. The CTC currently applies only to children up to age 16. Expanding eligibility to include 17- and 18-year-olds, as the EITC does, would extend benefits to roughly 8.3 million dependent children—1 million of whom live in poverty and would benefit substantially from the additional income.

Another key design issue concerns when benefits begin phasing in. The current CTC starts at earnings above $2,500, whereas the EITC begins with the first dollar of income. This matters greatly for low-income families. For example, with a 15% phase-in rate, a family earning $15,000 would receive $1,875 if the CTC began after $2,500 in earnings but $2,250 if it began immediately—a $375 difference that can be vital for the 5.7 million children in households earning below $15,000. The gap would be even larger with a steeper phase-in rate.

Finally, restoring monthly or periodic payments, as in 2021, would help families meet ongoing expenses such as rent, food, and utilities, improving financial stability throughout the year.

Conclusion

The EITC and CTC are two of the most effective and evidence-based policies ever enacted to support American families. They reward work, reduce poverty, and improve children’s long-term outcomes—all while enjoying broad bipartisan support. Yet millions of families remain excluded from full benefits because of design flaws, administrative hurdles, or incomplete refundability. Strengthening these credits—by expanding access, simplifying delivery, and ensuring full benefits for all children—would not only cut poverty but also reaffirm a simple truth: economic opportunity for families is a choice we make through policy.

The impact of these credits were largely offset by the elimination of personal exemptions.