How Tougher Immigration Enforcement Can Undermine Public Safety

New research finds that immigrant deportations can increase crime, through reducing victim engagement with law enforcement

President Trump campaigned in 2024 on the promise to conduct “the largest deportation program in American history.” The Trump administration has pursued this goal, deporting more than 600 thousand immigrants in 2025. A stated objective of this policy has been to improve public safety by prioritizing the deportation of undocumented immigrants with criminal records, though recent data indicate that nearly three-quarters of deported individuals had no criminal conviction prior to removal.

The general argument that immigration enforcement will improve public safety is often accepted as fact. In a 2024 Pew Research survey, over half of Americans believed that increased migration was leading to more crime and supported increasing deportation actions against immigrants. This argument is based on the idea that removing offenders through deportation will prevent them from committing crimes and also deter future criminal activity among others. While this logic is reasonable on its face, there are other potential ways that immigration enforcement could impact crime.

A heightened focus on immigration enforcement could undermine public safety if it creates fear among victims and community members. Victims of crimes could become reluctant to report incidents to police because they fear that they or a loved one could be deported as a result of interacting with law enforcement. When fewer crimes are reported, police are less able to identify, prevent, and solve crimes when they occur, making it harder to apprehend offenders. As a result, offenders may perceive a lower risk of being arrested for any crimes they commit and could actually increase their criminal behavior.

Indeed, our research on a past period of intensified immigration enforcement finds that increased deportation actions led to reduced victim and community engagement with police, and to increases in crime.

New research shows that a program that expanded U.S. immigration enforcement actually increased crime

In new research, we investigate how a relatively recent historical expansion in deportations impacted crime.1 Specifically, we study the Secure Communities program, a federal policy first established in 2008, that permitted the rapid detection of likely undocumented individuals who had been arrested for crimes. This program automatically forwarded the fingerprints of all individuals booked in local county jails to the Department of Homeland Security (DHS). DHS could thus check the immigration status of every person arrested by local law enforcement in the United States. If an arrestee was flagged as likely undocumented, the Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) agency could then issue a “detainer” request (or an immigration hold) asking local officials to keep the individual in their custody until they could be transferred to federal authorities. The Secure Communities program was rolled out across counties between 2008-2013, at which point the entire nation was covered by the policy. Immigrant detentions and deportations increased dramatically following the launch of the program. We estimate that the number of individuals transferred from local county jails to ICE custody doubled between 2008 and 2012. Overall, the Secure Communities program was responsible for the deportation of over 400,000 individuals between 2008 and 2014.

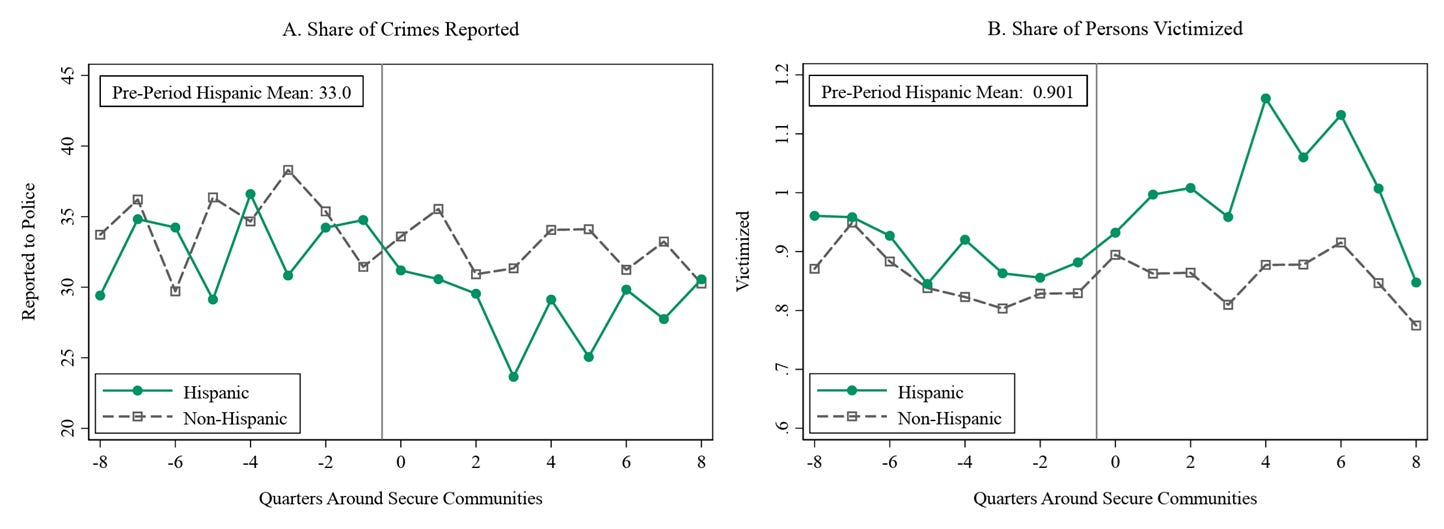

Figure 1: Expanding Deportations Decreased Victim Crime Reporting and Increased Crime: Impacts of Immigration Enforcement Program on Victim Reporting and Crime, by Hispanic Ethnicity

Note: Panels A and B plot the raw means of outcomes using National Crime Victimization Data (NCVS) around the date of implementation of the Secure Communities program.

We find that the Secure Communities program reduced the likelihood that Hispanic victims of crime reported the incidents to police. After the Secure Communities program was implemented in a county, Hispanics were 30 percent less likely to report crimes to law enforcement. The reporting decline occurred relatively quickly and appears more prominent among property offenses, such as burglary and theft. The fact that the policy affected Hispanics specifically is consistent with the program’s realized focus on the Hispanic community; over 90% of Secure Communities detentions and deportations were for individuals of Hispanic ethnicity. In contrast, we find no changes in the reporting behavior of non-Hispanics (see Figure 1 Panel A).

We also find that the policy increased crimes perpetrated against Hispanic victims. Hispanic victimization (or offending against Hispanics) increased by 16% (see Figure 1 Panel B). These estimates imply that Secure Communities resulted in 1.3 million additional crimes in the two years following the onset of the program. Again, the increase in crimes appears to be concentrated among property offenses, which comprise the majority of crimes. We observe no change in the overall victimization of non-Hispanic individuals after the implementation of the Secure Communities program. There is, however, an increase in the victimization of non-Hispanics who live in Hispanic communities (or areas with a high share of Hispanic residents). In contrast to the intended goal of the program to reduce crime, our estimates can rule out that the policy led to public safety improvements in the total population.

How do we distinguish between total crimes and reported crimes?

We calculate our main effects on crime and victim reporting behavior by comparing outcomes in counties that implemented the program earlier versus those that implemented the program later. Critically, we evaluate crime reporting behavior separately from changes in victimization to accurately measure the full impact of the policy on public safety. To measure crime reporting, we use the National Crime Victimization Survey (NCVS), a nationally representative annual survey of approximately 240,000 persons maintained by the U.S. Census Bureau. The NCVS asks respondents whether they have been the victim of a crime and, if so, whether they reported this crime to police. Unlike administrative police data, which only measures crimes that are actually reported to police, the NCVS has the advantage of being able to track all victimizations, whether or not they are reported. The NCVS also includes the ethnicity of respondents, allowing us to separately estimate effects for Hispanics.

Results show that the reduced willingness to report crimes to the police drives the increase in crime

These findings, while perhaps surprising, are consistent with the experience of law enforcement on the ground and effects in other contexts. Indeed, police chiefs have expressed concerns that increases in deportations decrease victim engagement and make the job of policing more difficult. Relationships that officers make and maintain with community members are critical to maintaining public safety.

In other contexts, there is evidence that exposure to police-involved shootings reduces civilian crime reports to police and that high-profile acts of police violence erode community engagement. In the setting of domestic violence, where victims have close relationships to offenders, victim reporting can be particularly responsive to changes in policing and enforcement practices. In particular, laws that require police to arrest abusers when a domestic incident is reported seem to have the unintended consequence of increasing intimate partner homicide, potentially because victims are less likely to contact the police.

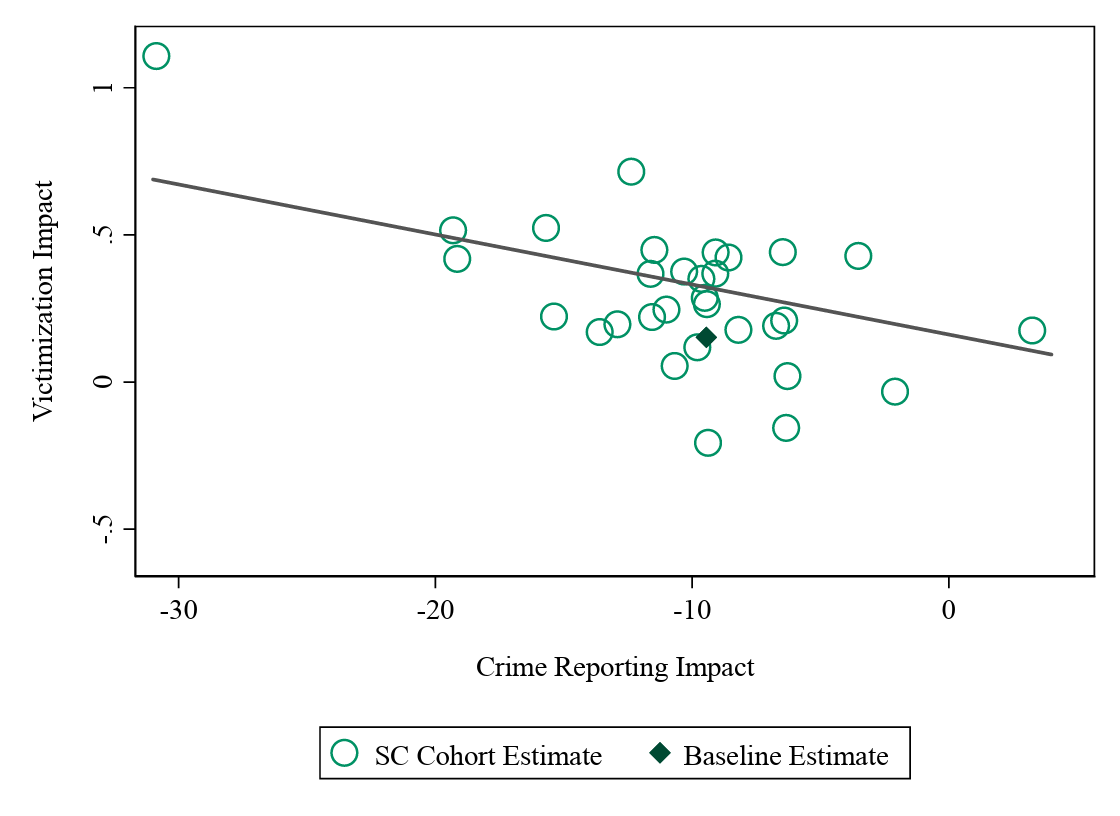

We examine this mechanism more carefully in the context of the national-level effects of the Secure Communities program described above. If increases in crime are the result of reduced civilian engagement with police, we should expect that areas across the U.S. that experienced greater declines in reporting also experienced the largest increases in crime. Indeed, we find that counties with larger declines in crime reporting rates following the Secure Communities program experienced larger increases in victimization rates (see Figure 2).

Figure 2: Counties with Larger Decreases in Victim Crime Reporting Have Larger Increases in Crime:

Note: This figure plots the impact of Secure Communities (SC) on crime/victimization effects against the impact on crime reporting separately for each Secure Communities cohort using NCVS data. A cohort refers to counties that activated Secure Communities in the same year and month. The diamond marker refers to the estimates that group all cohorts (or the total national estimate). Additional details on calculations can be found in the research paper.

Note that because the increase in victimization coincides with the decline in crime reporting, the overall rate of reported crime does not change after the launch of the program. This finding echoes the results of previous studies that found that Secure Communities did not have any measurable impact on rates of reported crime using administrative police data (see here, here and here).

Consistent with our work, prior research has shown that Secure Communities caused individuals, both citizens and non-citizens, to change their behavior in other ways that were likely motivated by fear of deportation. Secure Communities decreased Hispanic employment, by heightening the perceived risk of participating in the formal labor market within immigrant communities. Additionally, studies have found that Secure Communities reduced participation in the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) and in the Supplemental Security Income (SSI) program among qualifying Hispanic-headed citizen households. The onset of the Secure Communities program has also been linked to reduced workplace safety complaints to government regulators and increased injuries at workplaces with Hispanic workers.

Although Secure Communities had measurable impacts on a broad set of outcomes, we argue that the decline in victim reporting is the main driver of the observed increase of crime by ruling out other channels. First, one alternative story for the crime increase we observe could be that because Secure Communities decreased Hispanic employment, it could have led to an increase in property crime by Hispanic offenders as a substitute for lost wages. However, we find that the share of arrestees who are Hispanic declines following the Secure Communities program, implying that the increase in crime is not driven by an economic motivation to commit offenses by newly unemployed Hispanic offenders. In a related exercise, we ask: how large a crime response would we expect if Secure Communities only affected labor market outcomes and household composition, but did not account for any changes in victim crime reporting? Drawing on estimates from the existing academic literature, we show that the predicted effects on crime due to these alternative channels are quite small compared to the actual crime increase we observe. Similarly, we calculate that if the Secure Communities program only incapacitated and deterred offenders – without altering victim crime reporting – we would have anticipated an 11% decline in crime, in contrast to the 16% increase that occurs following the onset of Secure Communities. Overall, our research suggests that the decline in overall apprehension risk, driven by victims reporting fewer crimes, is responsible for the increase in crime.

The increase in crime we find following a historic rise in deportations is likely applicable to current immigration actions

Enforcement policies are often designed to change the incentives that offenders face, and we expect that harsher penalties will prevent or deter offenders from committing crimes. But offenders are not the only group that may respond to expansions in enforcement, as community members and victims may also change their behavior in important ways. In the context of immigration policy, intensified deportation efforts can generate fear among victims and discourage them from interacting with police. When crimes go unreported, police are less effective at apprehending offenders, which can have the unintended consequence of increasing crime.

Current deportation efforts by ICE are less targeted toward criminal offenders than in the Secure Communities time period. The Secure Communities policy that we study was relatively focused on offenders, in the sense that referrals to ICE originated in local jails and applied to immigrants arrested for offenses. During the Secure Communities time period, 20% of individuals transferred to ICE custody were not charged or convicted of any offense, whereas in 2025, over 70% of individuals deported by ICE were not charged or convicted of any offense. Our work implies that declines in trust in police and reduced public safety are likely to be more pronounced under deportation policies that do not focus on the most serious offenders, but instead cast a broad, unpredictable, or indiscriminate net across immigrant communities. It is in these cases where immigration enforcement is most likely to engender widespread fear and degrade community trust.

Gonçalves, Felipe, Elisa Jácome, and Emily Weisburst. 2023. “Community Engagement and Public Safety: Evidence from Crime Enforcement Targeting Immigrants.” (Conditionally Accepted, American Economic Review).