How Cuts to the Insurance Marketplaces Will Harm Entrepreneurs

Small business owners and the self-employed rely on the marketplaces, and coverage is about to become less affordable

The One Big Beautiful Bill Act (OBBBA) is projected to cause millions of Americans to lose health insurance. The Congressional Budget Office (CBO) projects that the $800 billion in Medicaid cuts over the next ten years will increase the number of uninsured by roughly 10 million. The OBBBA’s impacts on Medicaid have justifiably received much attention, as they will represent the largest reduction in enrollment in the program’s history. However, less attention has been paid to how the OBBBA will harm another important source of health insurance coverage: the Affordable Care Act (ACA) Marketplaces.

The OBBBA allows Marketplace premium subsidies to lapse at the end of this year and introduces new administrative barriers to obtaining Marketplace coverage. The CBO projects that, together, these policy decisions will result in 5.1 million additional people losing health insurance coverage. Millions more with marketplace coverage will face markedly higher health care costs due to higher premiums and lower benefits. While OBBBA’s Medicaid cuts will not take effect until after the 2026 midterm elections, the changes to Marketplace coverage will happen in January 2026. Indeed, the impact of these cuts can already be seen in the double-digit premium increases that many health insurers have announced for 2026.

Both the Medicaid and Marketplace cuts were made to finance tax cuts that disproportionately benefit the wealthy.1 But actions that make Marketplace coverage less affordable don’t just exacerbate inequality and limit access to healthcare. As we show below, the Marketplaces have proven to be an especially important source of health insurance for America’s small business owners and the self-employed. Thus, the resulting increase in marketplace plan premiums also harms entrepreneurs by markedly raising operating costs and exposing small business owners to increased medical spending risks.

Marketplace Insurance and its Importance to Entrepreneurs

The vast majority of Americans with private health insurance receive coverage through their own employer or the employer of a family member. The link between the workplace and health insurance coverage arises from the tax exclusion of employer payments for health insurance as well as efficiencies associated with large group purchasing. Historically, health insurance purchased by self-employed workers did not receive the same tax advantage as employer-sponsored group coverage. In addition, small businesses could not achieve the same efficiencies from economies of scale and risk pooling as large employers. As a result, self-employed workers and employees of small businesses were significantly less likely to have health insurance than otherwise similar wage and salary workers. Prior to the passage of the ACA, limited access to affordable health insurance was found to reduce entrepreneurship.

To make non-group coverage more affordable and to improve risk pooling, the ACA established premium tax credits for purchasing coverage through newly created individual insurance Marketplaces. These premium subsidies effectively capped the price of a benchmark plan to a fixed percentage of income for consumers with family incomes between 100 and 400 percent of the Federal Poverty Level (FPL).2 The 2021 American Rescue Plan (ARP) made Marketplace coverage even more affordable by increasing the premium subsidy for consumers who were already eligible and newly extending eligibility for subsidies to consumers with incomes above 400 percent of FPL. The Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) of 2022 extended these enhanced subsidies through 2025. These subsidy enhancements were an important reason that Marketplace enrollment more than doubled between 2020 and 2025, increasing from 11.4 million to 24.3 million.

Since they were established in 2014, the ACA Marketplaces have been an important source of health insurance for small businesses. To put this in perspective, self-employed workers, alone, represent about 10% of the U.S. workforce. According to data from the Census Bureau, 23% of working-age self-employed entrepreneurs had individual insurance market coverage in 2024–roughly four-times more than the fraction of working-age wage and salary workers that have individual market coverage.3,4 As a result, self-employed entrepreneurs and small business owners comprised nearly 30% of working-age marketplace enrollment in 2022, according to the Treasury Department.

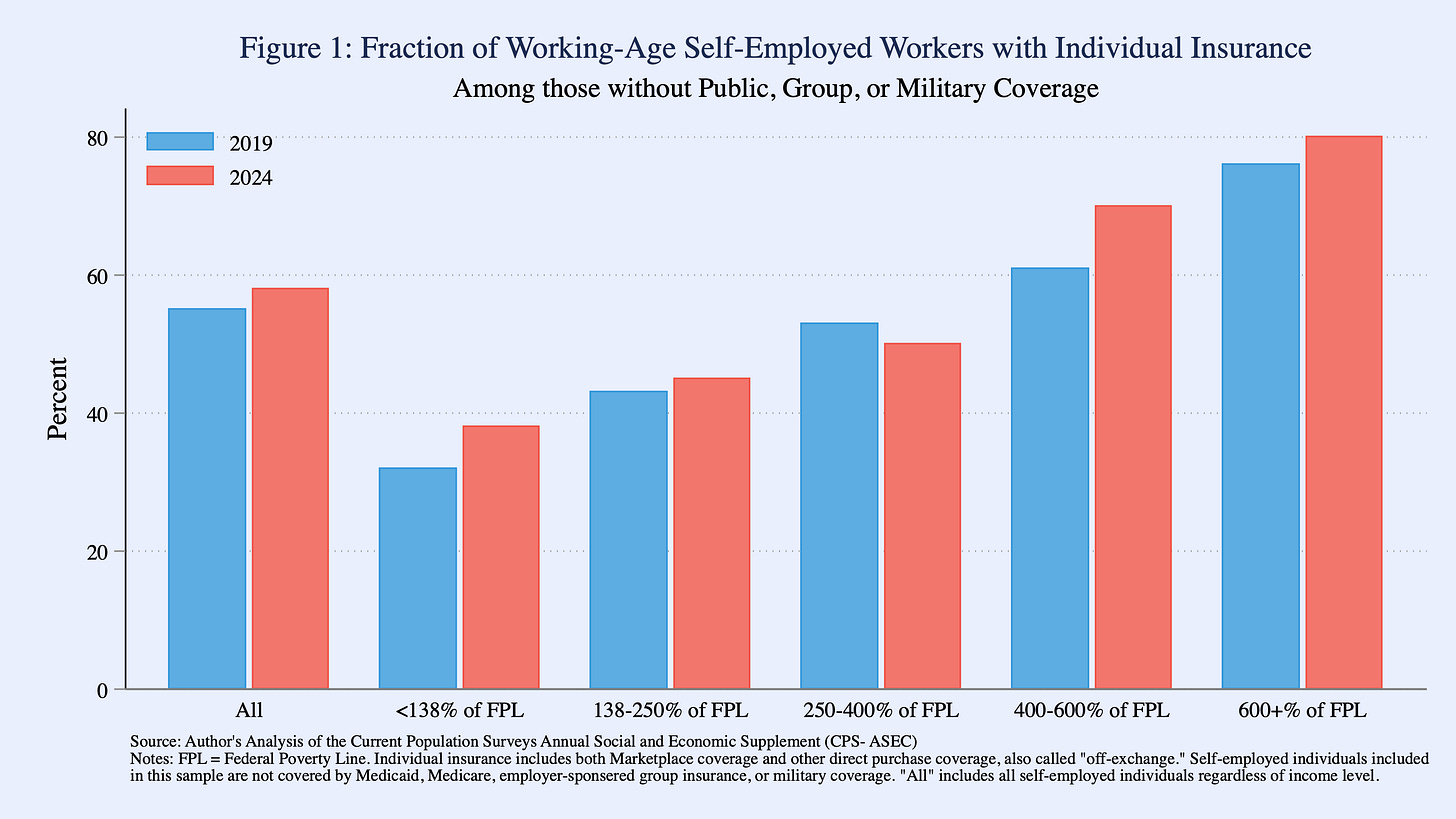

Access to Marketplace coverage is especially valuable for individuals who lack alternative coverage options, such as public insurance and or employer-sponsored coverage. Nearly 60% of working-age self-employed entrepreneurs who lack alternative coverage options rely on individual market insurance, or would likely be uninsured (Figure 1). An even greater percentage of middle-class entrepreneurs—those with incomes between 400% and 600% of the FPL–who lack alternative coverage options rely on individual market coverage.

Moreover, individual market coverage for these self-employed entrepreneurs has been increasing recently across most income groups, most of all among those with incomes above 400% of the FPL—those who gained eligibility for Marketplace premium subsidies under the ARP and IRA. In 2024, roughly 20% of all self-employed workers had family incomes above 400% of the FPL. Among those with incomes between 400-600% of FPL and no alternative source of coverage, 70% obtained coverage on the individual market that year, up from 61% in 2019. In 2024. For those with incomes above 600% of FPL, 81% relied on the individual market in 2024, up from 76% in 2019.

Effects of the OBBBA on Health Insurance Marketplaces

The OBBBA weakens Marketplace coverage in two ways. First, while the law extended several different tax cuts that were set to expire, it failed to extend the enhanced premium tax credits of the APRA and IRA. As a result, the amount that consumers are required to pay for Marketplace coverage will increase dramatically. One analysis, using data from HealthCare.gov, estimates that if gross premiums stayed the same and the tax credit enhancements were allowed to expire, net premiums for consumers currently receiving tax credits would nearly double on average.

But gross premiums will not remain constant. Because we can expect consumers who maintain their coverage in the face of such large premium increases to be more costly to insure than those who drop coverage, insurers will raise premiums to cover their costs. As noted above, insurers are already incorporating this “adverse selection” into their 2026 rates.

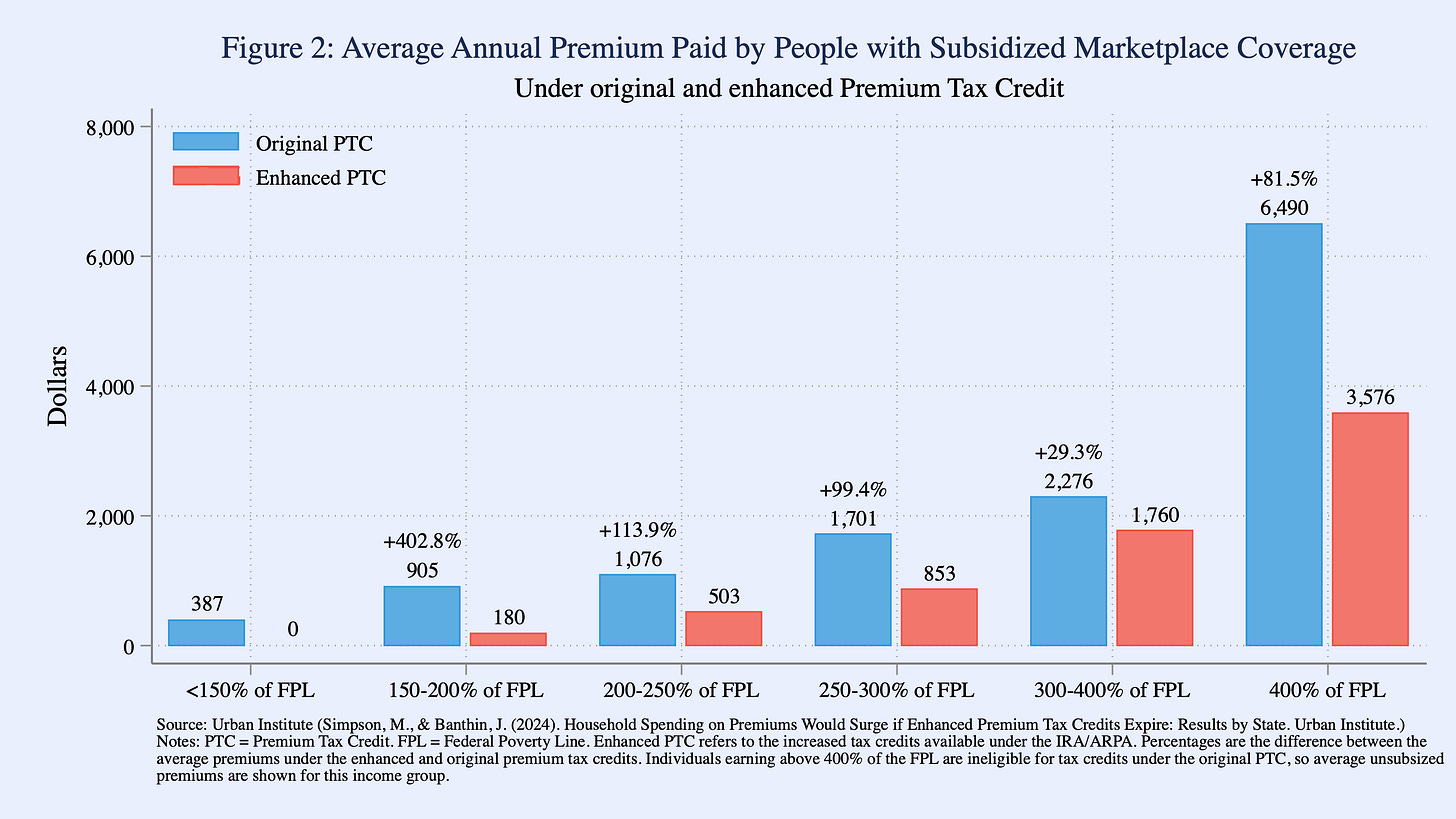

The exact impact of allowing the tax credit enhancements to expire will vary across geographic markets and consumer characteristics, most notably income and age. Figure 2 reproduces analysis by the Urban Institute estimating average annual premiums for different income groups with and without the enhanced premium subsidies. Their microsimulation accounts for the premium effects of adverse selection, and indicate that individuals whose income is above 400% of the FPL will be hit especially hard: with the loss of enhanced premium subsidies, the average annual consumer price for a plan will rise roughly $2,900, or by 81%. As noted above, roughly one in five self-employed workers has an income greater than 400% of the FPL.

Beyond cuts to premium subsidies, the OBBBA makes it more difficult to get insurance, adding administrative burdens to obtaining or maintaining Marketplace premium subsidies. For one, the legislation requires that eligibility for subsidies must be verified prior to renewing existing coverage, rather than after, effectively eliminating automatic coverage renewal. OBBBA also limits subsidy eligibility within special enrollment periods, and greatly restricts the flexibility of state-based Marketplaces to streamline their processes. As noted above, CBO projects that the Marketplace provisions of OBBA combined with other administrative changes, such as shortening the annual open enrollment period, will cause an estimated 5.1 million people to lose health insurance coverage.

Harms of the OBBBA go beyond the lost marketplace coverage for millions of Americans. Facing higher premiums, those who retain coverage will either pay more for coverage, or downgrade to a less generous plan with fewer benefits, or both, thereby raising medical costs. ARPA and IRA enhanced premiums led to marked increases in upgrading from high deductible Bronze plans to Silver, Gold or Platinum plans, which have much lower deductibles.

The Bottom-line for Self-Employed Entrepreneurs

For all consumers who have turned to the Marketplaces for affordable health coverage, these changes will represent a significant financial shock, with real implications for their health. For small-businesses and self-employed entrepreneurs, specifically, the OBBBA’s health care cuts could be even more financially damaging, threatening the health of their business.

Insurance premiums have risen as a share of total operating expenses in recent years, but Marketplace subsidies have helped moderate premium growth for eligible firms. Lower subsidies combined with large premium increases will force entrepreneurs to make difficult decisions. A recent study by JP Morgan Chase finds that fewer nonemployee firms (i.e., self-employed businesses) dropped health insurance coverage because of high premiums in 2022-23, when enhanced tax credits were available, than in 2018-19, when they were not. As coverage through the Marketplaces becomes less affordable, would-be entrepreneurs may once again face a difficult choice between launching a business or maintaining health insurance.

According to the Joint Committee on Taxation, the 194,000 filers in the top 0.1% will collectively see their taxes cut by about $50 billion in 2027, equal to the tax cuts accruing to the 95 million filers who represent the bottom half of all taxpayers.

In 2025, the FPL is $15,650 for a single individual, $21,150 for a married couple, and $32,150 for a family of four.

Data are from the Current Population Survey’s Annual Social and Economic Supplement (ASEC). Individual coverage includes Marketplace coverage, for which consumers can use Federal premium subsidies to lower costs, as well as other direct purchase insurance, often called “off-exchange” plans. While the ASEC does not accurately distinguish between these two types of individual coverage, an analysis of administrative data suggests that the ACA Marketplaces account for the vast majority of individual coverage. Working-age is defined as 19-64 years old.

The CPS-ASEC uses a strict definition of self-employment—those whose longest employment type in a year is self-employed—to capture individuals whose main form of labor is their entrepreneurial activity.

Totally correct. Several times I had ideas that I wanted to pursue via creating a startup company. But, with wife and young child, the cost of insurance prohibited me from leaving my job

Additionally, several times I wanted to change jobs to smaller, riskier companies but either the cost of paying the deductible again in the same year or the quality of coverage was so different as to make the change a non-starter

Thanks for this. This isn't just some partisan hype. My wife and I are in the same boat, and have been calling our Congressman regularly to do something about it.

This affects workers who don't get their insurance from their employer, including:

- Independent building trade contractors (electricians, plumbers, general contractors, etc.)

- Entrepreneurs starting their own business

- Realtors

- Local independent accountants

- Local independent attorneys