The Dangers of Shared Corporate Leadership

When the same person holds leadership or board positions at two competing companies, the companies are more likely to enter into collusive agreements

Common leadership is prohibited in many cases, but that prohibition has rarely been enforced

In the corporate world, members of the board of directors are often sourced from the leadership teams (boards or executive suites) of other companies. This means that serving multiple companies at once is not uncommon. Among US public companies, more than a third share a leader with at least one other public company—more still if start-ups and other non-public companies were included.

When two companies connected by such a common leader compete in the same space, this raises concerns that coordination by the two companies will weaken competition. The “opportunity and temptation” to coordinate can result in companies with common leadership setting higher prices, or limiting the choice or supply of products, to the detriment of the public. Such coordination is more lucrative the greater the competitive overlap between two companies, so it is perhaps concerning that a disproportionate share of common leadership links are to companies in the same industry.

US antitrust law includes a prohibition on many such common leadership links. Specifically, Section 8 of the Clayton Act forbids common leaders for companies with competing product lines. Based on this rule, antitrust enforcers last year pressured Microsoft to relinquish its seat on the board of OpenAI. Both companies ostensibly compete in the artificial intelligence space. The overlap triggered concerns among antitrust enforcers that Microsoft’s presence at OpenAI’s deliberations would make it easier for the two to coordinate, resulting in fewer or less safe AI product choices for the public.

However, until very recently, Section 8 was rarely enforced. In part, this was due to lobbying by corporations, which complained about the difficulty of finding qualified directors. It also seems to have been fed by a lack of evidence linking common leadership to anticompetitive behavior. In theory, shared information and incentive alignment can trigger or facilitate collusion. But does that really mean common leadership fosters collusion?

Below, we discuss new evidence showing a strong link between common leadership and anti-competitive behavior. In our study, the arrival of a common leader between a pair of companies raised the probability of later collusion by a factor of nine.1 These results provide backing for enforcers’ renewed interest in enforcing Section 8’s prohibition against competing companies sharing leaders. They also raise questions about Section 8’s current restriction to large product market competitors, as we show anticompetitive effects extend to cases where the current restriction does not apply. We return to potential policy implications at the end.

Common leadership predicts collusion

To understand whether enforcing against common leadership is likely to reduce collusion, we look to labor hiring policies. Labor is one of the most expensive inputs for most companies, and consequential for a company’s productivity and profitability. We study the largest known modern case of labor market collusion in the US.

In the mid-2000s, dozens of tech (and other) companies entered into no-poaching agreements: agreements not to recruit one another’s employees. The agreements involved high-profile companies including Apple, Google, Intel, and Genentech. They were eventually discovered by the Department of Justice (DOJ), which launched an investigation in 2009. The investigation led to a DOJ lawsuit and a series of follow-on civil court cases. By the time the legal dust settled, 65 companies were revealed to have been involved when the presiding judge released an unusually detailed trove of evidence from multiple court cases.

Unsealed court evidence allowed us to construct an analysis of over 900 pairs of companies—including both pairs that colluded and pairs that did not. For example, Pixar, Apple, and Google all feature among the colluding companies, because Pixar colluded with Apple, and Apple colluded with Google. Pixar and Google did not collude with each other, and that absence of collusion is also informative. All of the companies we study were thoroughly investigated for collusion with other companies in the sample, so we can also be more confident than usual that pairs not found to have colluded truly did not collude. Our analysis follows all 900-plus pairs of companies (including Pixar-Apple, Apple-Google, and Pixar-Google), tracking if and when they start to collude. Since collusion is meant to stay hidden, academic studies often need to infer collusion from other outcomes, like prices or auction behavior, and it is difficult to be certain whether two companies colluded or not. Thanks to the unsealed court documents, we have a direct measure of collusion from emails and internal memos documenting the agreements.

Akin to comparing “treatment” and “control” subjects in a medical study, we compared patterns of collusion among pairs of companies that recently began to share a common leader to other pairs that did not. We controlled for factors that might drive a company to collude more or less at a given point in time, such as new product launches that make collusion difficult to sustain. We also controlled for any factors that might drive collusion between a pair of companies, such as the similarity of their products or target markets.

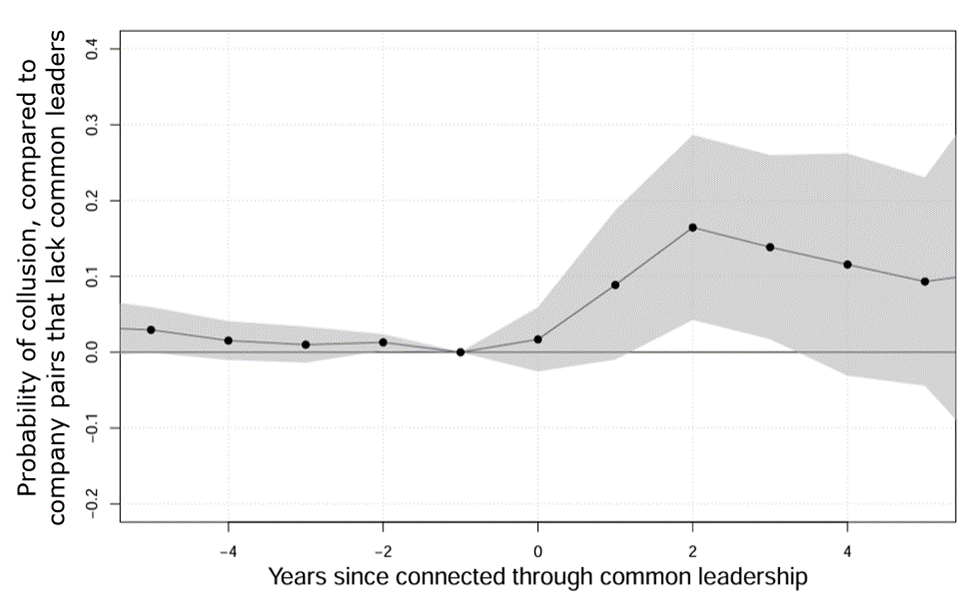

The figure below shows that the probability of collusion among company pairs that eventually get a common leader initially follows the same pattern as among “control” pairs that do not, up until the arrival of the common leader. Once the common leader arrives, the trajectories diverge, with company pairs with common leadership becoming more likely to collude.

Probability of Collusion Rises by 11 Percentage Points After Onset of Common Leadership

Note: Event study showing the probability of collusion increases in the years after pairs of companies become connected via common leadership. The regressions include company pair and company-by-year fixed effects to account for competitive overlap within company pair, and company trends that could also influence the probability of collusion.

We find that the probability of a no-poaching agreement rises by 11 percentage points following the onset of common leadership. This is a ninefold increase in the probability of collusion over the baseline rate of 1.2 percent in the absence of common leaders. Some of the companies involved paid over $400 million in a settlement in the case.

Common leadership is a useful marker for difficult-to-detect illegal behavior

Collusion is ordinarily difficult for antitrust enforcers to detect. Because of its secretive nature, it is difficult even to estimate the prevalence of undetected collusion. At the same time, collusion is recognized as one of the most clearly harmful types of economic behavior. The law treats collusion as per se illegal, meaning the presumption of harm from collusion is so great that courts do not require prosecutors to demonstrate specific harms. It is sufficient merely to show that collusion took place, and harms are assumed. Given the high social costs of collusion and the difficulty of detecting it, a tool that gives antitrust enforcement agencies an easy way to reduce collusion can be very valuable. Our findings show that enforcing the prohibition against common leadership may be such a tool.

Of course, not every common leadership link is accompanied by collusion. Even in our sample, most company pairs that share leaders did not have no-poaching agreements. Moreover, there are reasons to think that the relationship between common leadership and collusion across the entire modern economy is smaller than in our sample. Because of our data source, our sample likely overrepresents “bad apples,” or companies that are more willing to collude than a typical company. We also study a time period with laxer antitrust enforcement. Common leadership is not a smoking gun, but the direction and strength of its relationship with collusion is notable.

Antitrust enforcers are right to step up scrutiny of common leadership

Our new findings carry two important implications for modern antitrust enforcement. First, they provide empirical support for the renewed interest that enforcers have shown in using Clayton Act Section 8 to police interlocking directorates. The 11-percentage point increase in the probability of collusion following the formation of a common leadership tie suggests that Section 8 enforcement can serve as an effective tool for reducing opportunities for coordination.

Second, our results raise questions about Section 8’s current limitations. At present, Section 8 applies only to interlocks between large companies that compete in product markets. But the anticompetitive effects we observe extend beyond product market competitors. In our study, many pairs of companies that colluded were not product market competitors; some competed in labor markets, and others barely seemed to compete at all.2 To the extent that common leadership facilitates collusion by providing a discreet communication channel and a way to set and enforce common goals, it can facilitate collusion in labor markets and other input markets, not just product markets.

These findings suggest a path toward more focused antitrust enforcement by the DOJ’s sister agency, the Federal Trade Commission (FTC). The FTC, which benefits from more preemptive oversight tools than the DOJ under Section 6(b) of the FTC Act, could use the prevalence of common leadership as a screening metric when selecting industries for market studies. Investigating such markets may allow the FTC to catch emerging collusive risks earlier.

Overall, our results suggest that although common leadership is not always accompanied by collusion, it is a meaningful predictor of collusive risk. This makes it a potentially powerful lever for proactive antitrust enforcement—not only under the existing structure of Section 8 but also in potential reforms that broaden its scope or create analogous tools for labor and other input markets.

This post uses language that assumes allegations, documents, and evidence presented in a Complaint filed on September 24, 2010 by the US Department of Justice, and additional litigation, are true. The language we use reflects our subjective interpretation of those documents. It does not reflect any finding of any court or admission of guilt by companies discussed in this post.

For example, Apple colluded with J. Crew and Nike. Apple does not compete with either company in any meaningful market, but did share common board members with both companies. Apple’s internal documents suggest that the common board members were the reason for the “collusion of convenience” in these instances.