The coming debate over the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act

Expiring provisions and a changed fiscal and global tax landscape set the stage for an intense and consequential debate over tax policy following the election

The stakes for tax policy are high this election year. Even putting aside the proposals that have popped up during the silly season of tax policy this election year – such as not taxing tips, exempting the Social Security income of even the richest retirees from taxation, and replacing the entire income tax system with regressive tariffs that will almost certainly trigger retaliatory counter-tariffs – important decisions await the newly elected Congress and President. The expiration of key provisions of the 2017 Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA) will set off important and consequential debates that will shape the level and distribution of tax revenues in the United States.

The coming tax debate will center on the individual provisions of the TCJA, which are scheduled to expire in 2025. These provisions, which cut overall individual tax rates, changed taxable income deductions, and created lower tax rates for business owners, among other measures, must be renewed with new legislation and will thus be hotly debated. Already, the campaign trail has seen dueling proposals to expand the Child Tax Credit (CTC) and very different plans for tax rates at the top of the income distribution.

Although the business provisions of the TCJA were largely legislated to be permanent, scheduled tax increases opposed by some firms and industries, and interest among Democrats in returning corporate tax revenues closer to their historic averages make it likely that business taxes will be in hot contention as well. Further, weaker economic impacts than were anticipated may have dulled appetites for continuing these costly business tax reductions.

Because the TCJA had such outsized effects on the tax burdens of the highest income taxpayers, renewing individual provisions or adjusting the parameters of business tax changes, will largely affect tax bills at the top. For most taxpayers the largest impact of the TCJA has been easier tax filing due to the relatively larger standard deduction, rather than a material change in the amount of tax they owe. An important exception is the CTC, which in the years since the TCJA has found new roles in the policy agendas of both parties, and in either incarnation would mostly reduce the taxes of households outside the top brackets.

The budget impact of the TCJA and the need for new revenue

Next year’s tax debate will happen at a time when the US budget outlook is darkening. In the years since the TCJA’s passage the US debt has ballooned from roughly 75 percent to 96 percent of US GDP due to measures taken during the COVID-19 pandemic, but also due to the loss of revenues precipitated by the TCJA.

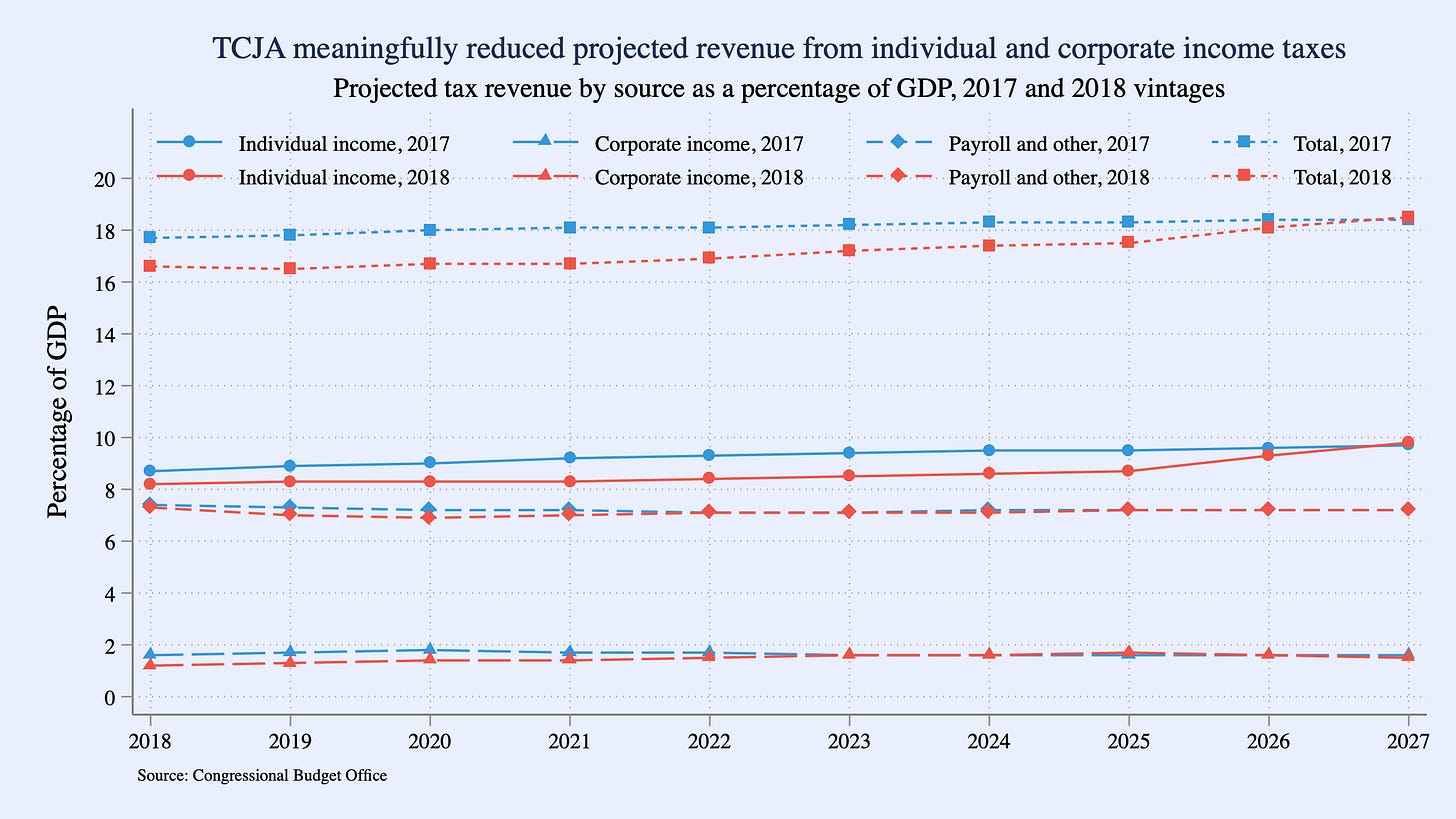

The net impact of the TCJA was to sharply reduce collected revenues, especially from corporate sources. In its last projections before the passage of the TCJA at the close of 2017, the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) projected that 2019 federal tax revenues would total 17.8 percent of GDP. Projections updated to reflect the TCJA in 2018 shaved 1.3 percentage points off the revenue projection. The TCJA cut the GDP share of corporate taxes by a quarter while reducing the GDP share of individual income taxes by about 7 percent.

Tax cuts not paired with spending reductions push the burden of today’s government into the future, effectively redistributing from future generations. Deficit spending may make sense for expenditures that are truly investments where a substantial share of the benefits accrues to future Americans, such as in the case of infrastructure, or where current generations make outsize contributions, such as in war efforts; and may even be true for measures taken during the COVID-19 pandemic to forestall economic disaster. This is less true of the provisions of the TCJA, which cut taxes precipitously without substantial gains in terms of long-run productivity or growth.

The need for revenue will shape the debates over the TCJA. However, Congress’s recent history of passing major tax legislation through the reconciliation process and thus subverting rules that prohibit such legislation from adding to the federal deficit may facilitate yet another tax bill that, on net, cuts taxes and sunsets after ten years.

Individual Income Tax Changes

The TCJA made significant changes to individual income taxes. Unlike the business provisions, most of the TCJA’s individual income tax code changes are scheduled to expire in 2025. Estimates from CBO and the Joint Committee on Taxation (JCT) indicate that making these provisions permanent will add $3.26 trillion to the deficit between FY2025 and FY2034. Of the many adjustments the TCJA made to the individual tax code, three will likely be the subject of intense debate. Because the individual rate reductions disproportionately benefitted higher income taxpayers while adding substantially to the deficit, adjusting the marginal tax rate on the highest-income taxpayers will be a top concern. The limitation on state and local tax (SALT) deductibility has led the TCJA to have disparate impacts in states with and without substantial income taxes, particularly among high-income taxpayers. These disparities have led lawmakers of both parties from high-tax states to advocate strongly for the limits repeal or expansion. Finally, Republicans and Democrats have distinctly different ambitions for the child tax credit (CTC), with those on the right advocating for a credit that primarily provides tax relief to the middle and upper-middle class while policymakers on the left want to harness the CTC’s demonstrated effectiveness in reducing child poverty to provide cash support to low-income households.

An Overview of the TCJA’s Changes to Individual Taxes

The TCJA reshaped individual income taxation in several ways. It reduced income tax rates and widened tax brackets, doubled the child tax credit, and created a new dependent care credit. Some of the TCJA’s most wide-reaching impacts, though, stem from its elimination of the personal exemption and changes to individual deductions.

The TCJA eliminated personal exemptions, nearly doubled the standard deduction, and limited itemized deductions, changing how taxpayers file their taxes and reshaping the national distribution of tax burdens. The TCJA also narrowed mortgage interest and SALT deductions. While prior to the TCJA, taxpayers could fully deduct any SALT paid from their federal taxable income, following the TCJA, the SALT deduction is limited to $10,000 per year for joint filers. Mortgage interest is now only deductible on the first $750,000 in principal value, where once interest on the first $1 million of principal was deductible. Also, the higher standard deduction made itemizing less attractive to many taxpayers and reduced the use of other common deductions, such as those for charitable giving and medical expenses.

The end result of these changes has been a very different pattern of tax filing. Roughly 30 million taxpayers shifted from itemizing their deductions to claiming the new standard deduction which rose from $12,700 to $24,000 for a jointly filing tax unit in 2018. For many taxpayers, opting for the standard deduction over itemizing various deductions simplified filing, reducing the complexity, error rates, and time needed to file.

It is well known that the benefits of the TCJA individual income tax cuts accrue disproportionately to those at the top of the income distribution, in part because they bear higher tax rates. Taxpayers in the bottom quintile of the income distribution (incomes of $25,000 or less) saw an average tax cut of $40 or 0.3 percent of after-tax income, while those in the middle quintile (incomes between roughly $49,000 and $86,000) saw their incomes rise by $780 or 1.4 percent of after-tax income, and among the top quintile income rose by $5,790 or 2.2 percent of after-tax income. This overall regressivity has prompted some policymakers, including the President, to call for returning to a top marginal tax rate of 39.6 percent.

The Modest Revenue Gains from Higher Tax Rates at the Top

While rolling back tax cuts for households with $400,000 in income or more has been a frequent talking point, analysis by TPC suggests this rate increase alone will raise only a modest amount of revenue. Raising tax rates on these tax units would have raised roughly $30 billion more in revenue in 2025, which is, for example, about a sixth of the cost of Vice President Harris’ proposed CTC.

Further revenue may also be raised by taxing more types of income at ordinary rates for high-income taxpayers. For example, TPC’s estimates indicate that taxing capital gains and dividends at the same rate as ordinary income for those with $1 million or more in annual income and taxing unrealized capital gain at death would raise roughly $51 billion per year. Even though the TCJA did not adjust capital income taxes, the coming tax policy debate may well lead Congress to examine the potential for new revenue and added progressivity from raising rates on dividends and capital gains taxes, at least among higher-income taxpayers.

A Changing Geography of Tax Burdens

Limits on SALT deductions have remade the geographic distribution of tax burdens, particularly among high income households. Which households gained most and least from the TCJA will, of course, naturally depend on differences in family composition and the types of income earned. Nonetheless, analysis by the Urban-Brooking Tax Policy Center (TPC) shows that SALT deduction limitations account for much of the variation in how the TCJA, and thus its expiration, impacted taxpayers in different states. In most states, the average change in after-tax income expected in 2018 was close to the national average of 1.8 percent, but five states (Alaska, North Dakota, South Dakota, Texas, and Wyoming) had substantially higher gains of at least 2.2 percent, while five (California, Washington DC, Maryland, New Jersey, and New York) saw substantially smaller gains of 1.7 percent or less. These differences are driven by state tax variation, with taxpayers in states with high income taxes and property values seeing smaller TCJA tax cuts due to the limits on state income and property tax deductibility. Four of the five states that saw the largest average TCJA tax reductions have no state income tax, while North Dakota has one of the lowest and flattest rate structures. States with smaller average tax cuts, on the other hand, are among those with the highest average and top income tax rates.

Differences in the tax bills of the highest-income households drive these state disparities. We can compare Texas, which has no state income tax, to New York, which has a top state marginal tax rate of 10.90 percent. While the average increase in after-tax income among taxpayers in the bottom 60 percent of the income distribution was very similar in Texas (1.9 percent), and New York (1.7 percent), among taxpayers in the 80th to 90th percentiles Texans saw much larger average after-tax income gains (2.1 percent) than New Yorkers (1.3 percent). For the top one percent, the average increase in Texas was 2.9 percent and just 1.3 percent in New York. The limit on SALT deductions also left 29 percent of the top one percent earners in New York with higher tax bills but raised taxes on just 5 percent of such earners in Texas.

The crux of the SALT limit is that it almost exclusively affects high-income taxpayers. Of the $650 billion in revenue generated over 10 years by the SALT limit, 96 percent is paid by the top fifth of taxpayers with the top one percent contributing 57 percent alone. These taxpayers, of course, have advocates in Congress and lawmakers of both parties from high-tax states can be expected to vociferously advocate to repeal the SALT limit. They may have a point. While the SALT limit is progressive, cutting the federal subsidy to state taxes undermines the funding stream for important government services. Half-measures to allow fuller SALT deductions for taxpayers with less than $400,000 in income will not address the ultimate impacts of no longer subsidizing the state tax contributions of high-income taxpayers that provide the bulk of state tax revenues.

Child Tax Credit

The TCJA doubled the child tax credit (CTC) from $1,000 to $2,000 and made up to $1,400 of the credit refundable ($1,600 in 2024) while also raising phase-out thresholds such that families with up to $400,000 in income received a child credit. The TCJA maintained the 15% phase-in rate of prior law but reduced the threshold for CTC eligibility to $2,500 from $3,000. On net the impact of the TCJA was to make the CTC a larger tax cut for families further up the income scale.

As part of its effort to shore up household incomes during the COVID pandemic, the American Rescue Plan Act (ARPA) of 2021 temporarily made the CTC far more generous. The credit amount was raised to $3,600 per child under age 6 and to $3,000 for children between 6 and 17 years and made fully refundable even to families with zero earnings – but just for 2021. The combination of full refundability and lower phase-out thresholds yielded a CTC that reached a little less far up the income distribution but provided vastly more resources to the poorest families. Child poverty fell sharply as a result. Estimates indicate extending the expanded CTC into 2022 would have raised 3 million more children out of poverty and reduced the child poverty rate by about a third from 12.4 percent to 8.4 percent.

Like most other individual provisions, the CTC is slated to revert to its pre-TCJA parameters, meaning a substantially smaller, phased-in but fully refundable $1,000 tax credit. The debate between a more generous CTC that primarily cuts taxes for middle and upper-middle-class families versus an ARPA-style CTC that substantively addresses child poverty will manifest in discussions of phase-in rates, refundability limits, and phase-out thresholds. Ultimately, the size and shape of the CTC will depend on which pieces of the TCJA that limit deductions and exemptions remain, but the demonstrated effectiveness of the CTC in reducing child poverty reframes the policy as more than a tool to adjust middle-class tax burdens. Many lawmakers see a phased-in CTC as an extension of the EITC, offering both negative tax rates to incentivize work among low-income families and providing added resources that can have lasting impacts on the long-term outcomes of children living in low-income homes. The form of the CTC that the 2025 tax debate settles on may reset the role of the CTC in US fiscal policy for decades to come.

Business Tax Changes

Unlike the TCJA’s generally temporary changes to the individual income tax code, its alterations to business taxes were by and large legislated on a permanent basis, meaning that most provisions dealing with business taxation will not expire in 2025. Changing the way businesses are taxed will require legislation that goes beyond which expiring provisions to renew.

In broad strokes the TCJA changed business taxes in two ways: 1) sharply lowering business tax rates and moderately widening the business tax base, and 2) moving from a worldwide to a territorial system of international business income taxation. The combined effect of these changes to how firms are taxed was a reduction in CBO’s projected corporate tax revenues from $324 billion to $243 billion, or 25 percent. Recent research pegs the corporate revenue decline at 40 percent.

Of the many business tax changes engendered by the TCJA, a handful are most likely to be revisited in 2025. These measures include the actual corporate tax rate, the limitation on interest deductibility, the curtailing of R&D subsidies, and the scheduled increases in international taxes.

Much lower rates, a somewhat wider base

The TCJA reduced the top corporate tax rate from 35 percent to 21 percent while eliminating the graduated corporate tax rate schedule and the corporate alternative minimum tax. The large rate reduction and resulting sharp decline in corporate tax revenue has led to calls to raise the corporate tax rate, for example Vice President Kamala Harris’ campaign and President Biden’s budget have proposed a 28 percent corporate rate. In contrast, former President Trump has proposed an even lower corporate tax rate of 15 percent for firms that produce products domestically, though it is unclear exactly how a firm would qualify for the lower rate.

To offset part of the revenue lost to lower rates, the TCJA limited some business deductions. After initially allowing full expensing of investments in assets with lives of 20 years or less, bonus depreciation has been phased out until it is fully eliminated after 2026.

Limits on interest deductions tightened in 2022 when rather than being able to deduct 30 percent of business income before interest, depreciation and amortization (EBITDA), firms were allowed up to 30 percent of income before interest (EBIT). This added limitation should hit firms with high depreciation and amortization costs, such as manufacturing and intellectual property-intensive industries, particularly hard. While these limits were legislated to be permanent, this is certainly an aspect of the TCJA that is likely to be revisited in 2025.

TheTCJA’s sharp reduction in business taxation had only modest effects on the capital stock and offered little benefit to the vast majority of workers. The TCJA led to increased corporate investment but largely fell short of its advocates’ predictions. Research indicates that the TCJA boosted U.S. domestic corporate capital by 6 percent in the long-run, which falls short of the Trump administration’s prediction that the tax package would raise the US capital stock by 12 to 19 percent. Moreover, estimates indicate that some of the TCJA’s smaller corporate tax reductions, such as bonus depreciation, were more effective in generating investment than the main cost drivers of the legislation.

Despite predictions that added investment spurred by the TCJA’s lower corporate rates would foster productivity growth and higher wages for ordinary workers with Trump administration officials suggesting annual increases of $4,000 and $9,000, research has found that the earnings of the bottom 90 percent of workers in a firm were not affected by the TCJA. Incomes only rose for the top 10 percent of earners with a firm, with particularly large increases for managers and executives that were only weakly correlated with firm performance measures like profits or sales growth. Other work indicates that the TCJA’s business tax changes raised economic growth and wages by much less than the legislation’s supporters argued it would, adding less than 1 percent to long-run GDP and boosting labor income by less than $1,000 per employee.

The TCJA created many tax advantages for smaller firms as well. It doubled the Section 179 expensing limit from $500,000 to $1,000,000 and firms with less than $25 million in gross receipts are exempt from the interest deduction limits. In an effort to lower the tax rates applied to pass-through business income, the TCJA allows owners of pass-through business with less than $383,900 in 2024 taxable income if filing jointly ($191,950 if filing singly) to deduct 20 percent of their qualified business income. The deduction reduces the effective top individual tax rate on pass-through income from 37 percent to 29.6 percent, much closer to the corporate tax rate of 21 percent. If taxable income exceeds the QBI deductibility threshold, the deduction is limited depending on whether the business provides personal services such as a medical practice or a law firm, the wages paid and the investment property owned. Researchers found little evidence that these tax cuts for pass-through firms led to changes in real economic activity in terms of physical investment, wages to non-owner employees or employment.

The TCJA made a handful of other smaller changes to the tax code, eliminating the domestic production activities deduction (Section 199), limiting the use of net operating losses and changing the parameters of the orphan drug credit among other narrow provisions. Perhaps most controversially, the TCJA reduced subsidies for R&D by requiring expenditures for research and experimentation to be amortized over five years if domestic and 15 years if offshore rather than being expensed. Concerns about federal support for innovation may lead Congress to examine these changes to federal R&D subsidies.

A Modified Territorial System

Among the most drastic changes of the TCJA is its treatment of the income earned abroad by US multinational corporations. Prior to the passage of the TCJA, the US had a worldwide tax system where all income earned by US multinational corporations, whether earned domestically or abroad, was taxed at the US corporate tax rate with credits for taxes paid to foreign governments. Taxes on the income of foreign subsidiaries, however, were deferred until the income was repatriated to the US parent company.

The TCJA moved the US to a modified territorial tax system where US corporations only owe US tax on domestic profits. Dividends paid to US parent companies from foreign corporations in which the parent holds at least a 10 percent stake are no longer subject to US taxes. To blunt the incentives to shift operations and income to low-tax foreign jurisdictions, the TCJA added a minimum tax on global intangible low-taxed income (GILTI) and a deduction for foreign-derived intangible income (FDII). The GILTI levies a 10.5 percent tax on returns over 10 percent earned on tangible property held abroad. The FDII provides tax benefits to holding intellectual property in the US by tax-exempting income earned from exporting products that use US intangible assets. The TCJA also introduced the base erosion and anti-abuse tax (BEAT), which subjects payments between US parent corporations and their foreign subsidiaries to a minimum tax to address the excessive use of transfer pricing and other methods to shift income to low tax jurisdictions.

With GILTI and BEAT rates scheduled to rise in 2026 – the same year that compliance with the OECD-led Pillar Two project is expected – international tax reform may well be on the agenda in 2025 despite the fact that the international tax provisions of the TCJA were legislated to be permanent. As GILTI and BEAT taxes provide much-needed revenue that helps trim the deficit impact of the tax package overall, it may be hard for lawmakers to cut these taxes. Research indicates, however, that the TCJA on net led US multinational firms to increase their foreign capital with some complementarity with domestic investment, suggesting that the move to a territorial system played out just as the incentives created by the GILTI and FIDII suggested it would.

In the seven years since the TCJA was passed, many of its provisions have proved controversial, and the coming expiration of many of its individual tax provisions will kick off a strident debate about how much revenue the federal government should raise and how it should raise it. The coming debate will likely focus on the individual and corporate rate cuts, the limits on SALT and other deductions, scheduled international tax increases, and the CTC but will also likely move beyond the specific provisions of the TCJA itself. Lawmakers of both parties have shown renewed interest in reformulating the CTC but with very different end goals. Arguments about whether the top individual tax rate should be higher or lower are also joined by new calls for changing dividend and capital gains taxes in light of a booming but potentially peaking stock market. Growing global cooperation over the tax treatment of multinational corporations may lead lawmakers to revisit US international tax provisions. Yawning deficits as far as CBO’s projections can see have also set the stage for more serious conversations about revenue. Tax policy will be front and center in the coming year and these debates will set the foundation for the overall progressivity and affordability of federal policy for decades to come.

Lots of good points but the fundamental one is that deficits > Σ(expenditures with NPV>0) very probably shift resources from investment to consumption and the reduced growth in income is the _way_ that deficits today burden future generations.