The Bank and Private Capital Shadow Venture

How to safekeep banks—and the safety net—from interconnections and systemic risk

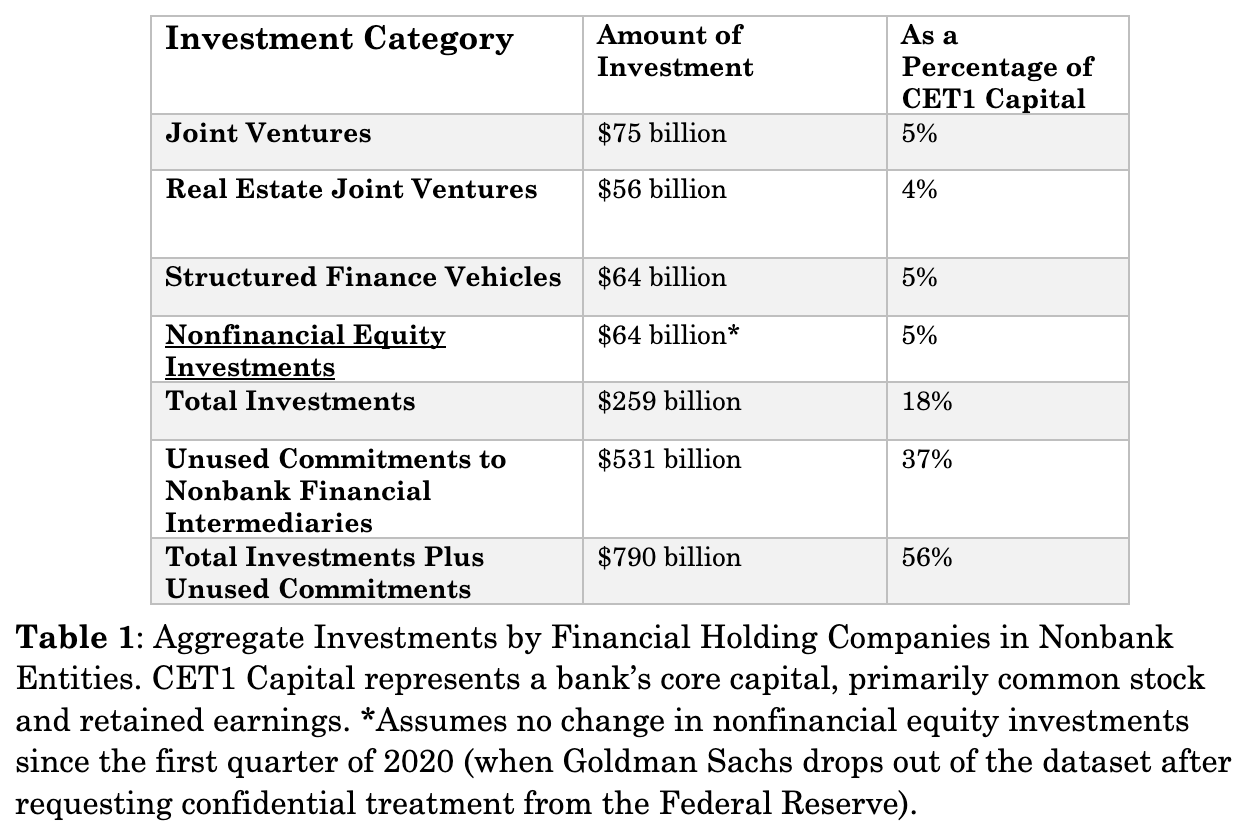

Since the 2008 financial crisis, banks and private capital have become deeply integrated through equity partnerships, liquidity commitments, and risk-transfer arrangements largely overlooked by existing scholarship and regulation. The integration takes place in the shadows outside the prudential bank regulation and off the banks’ balance sheets. The size of bank investment is economically significant, amounting to 18% of the largest banks’ common equity tier-1 capital (a bank’s core capital, primarily common stock retained earnings) of large banks—rising to 56% when unfunded liquidity commitments to nonbank financial intermediaries are included. This bank and private capital “shadow venture” creates systemic vulnerabilities, hidden risks, and warrants regulatory consideration of a menu of prudential reforms.

The Standard Account: Banks Pushed Risk Out to Shadow Banks

For nearly two decades, the organizing narrative of post-crisis financial regulation has been bank de-risking. Higher capital requirements, enhanced supervision, and the Volcker Rule supposedly forced banks to push risk into the unregulated shadow banking sector while increasing capital inside the banking sector.

But if the banking sector is de-risking, why are its largest players aggressively partnering with the riskiest actors in the financial ecosystem in off-balance sheet ventures?

The Rise of the Bank and Private Capital Shadow Venture

The most important development since the crisis is not separation between banks and shadow banks, but strategic convergence. In September 2024, JPMorgan Chase announced a $50 billion investment in its private credit partnerships—direct lending arrangements with at least seven asset managers where the bank provides capital and origination expertise while private funds make the loans. Citigroup and Apollo announced a $25 billion joint lending program. Wells Fargo took equity stakes in Centerbridge Partners’ direct lending funds. These are not isolated transactions—they represent a structural realignment of American finance.

In a recent article, I refer to these arrangements as a bank and private capital “shadow venture”: a set of equity stakes, contractual partnerships, liquidity backstops, and risk-transfer arrangements that link banking organizations to private funds outside formal consolidation and that are not subject to prudential bank regulation. The shadow venture is not “shadow banking” as a sector, but the interface through which banks increasingly participate in private markets. Like shadow banking, however, the shadow venture operates outside the regulatory perimeter. In the shadow venture architecture, banks do not merely lend to private capital. They increasingly become owners, partners, and backstop liquidity providers.

Private credit, in particular, has emerged as a locus of systemic concern. One article chronicles how private credit has caused debt markets to “go dark.” Researchers at the Federal Reserve found that bank lending to private credit vehicles increased more than ten times over the period of 2013-2024. In the United Kingdom, the House of Lords Financial Services Regulation Committee recently published a report on the growth of private markets, focusing on private credit.

Table 1 presents public regulatory data and data obtained from the Federal Reserve through a Freedom of Information Act request on aggregate investments by the banking sector in entities where a financial holding company holds a significant equity exposure as of the end of the third quarter of 2025. It also presents data on unused loan commitments to nonbank financial intermediaries.

These exposures are concentrated in the six largest banking organizations (JPMorgan Chase, Bank of America, Wells Fargo, Citigroup, Goldman Sachs, and Morgan Stanley) and represent approximately 56 percent of their combined common equity tier-1 capital when unused commitments are included.

Bank exposures to private capital have grown dramatically. Investments in unconsolidated joint ventures have increased fivefold since 2001. Real estate venture investments have grown tenfold over the same period. The structure of these investments is different than historical banking investments: they are made in entities where a banking organization has made a significant equity investment.

Why bank partnerships with private capital are increasing remains an open question. Functionalist theories assume that market relationships arise to solve information frictions and transaction cost problems. On this account, regulating these relationships would impose costs on efficient financial operations. But institutionalist theories counter that agents of the banks with conflicted incentives may exploit or even create market frictions. If the shadow venture is merely acting as a conduit for regulatory arbitrage—for banks to make loans and reduce capital in ways they could not do on balance sheet—then new regulation could provide net benefits. The too-big-to-fail moral hazard problem is of particular relevance if high-risk fund investments outside the regulatory perimeter operationalize high fee and high variance investments. The opacity of the shadow venture makes answering this question difficult. The investments are made off-balance sheet and the portfolio companies are almost all private entities.

Why This Matters: The Shadow Venture Creates Prudential Concerns

Hidden Interconnections and Systemic Risk

The bank-private capital integration creates transmission channels through which stress in private markets could propagate to insured banking institutions. There are recent, troubling precedents. In 2007 and 2008, private, nonbank asset-backed commercial paper conduits transmitted contagion and financial failure to the banking sector through liquidity lines and repo markets. In 1999, Long-Term Capital Management, a nonbank hedge fund stood on the brink of failure. Financial interconnections between Long Term Capital Management and the banking sector prompted the Federal Reserve to orchestrate an emergency private sector recapitalization and the Government Accountability Office to declare that “Regulators Need to Focus on Systemic Risks.” Unlike traditional lending relationships, equity partnerships and liquidity backstops in the shadow venture create contingent exposures that may not be fully reflected in current risk assessments or stress testing frameworks.

Who Bails Out Private Credit and Real Estate? Banks, Backdoors, and Risks of Expanding the Federal Safety Net for Banks to Private Funds

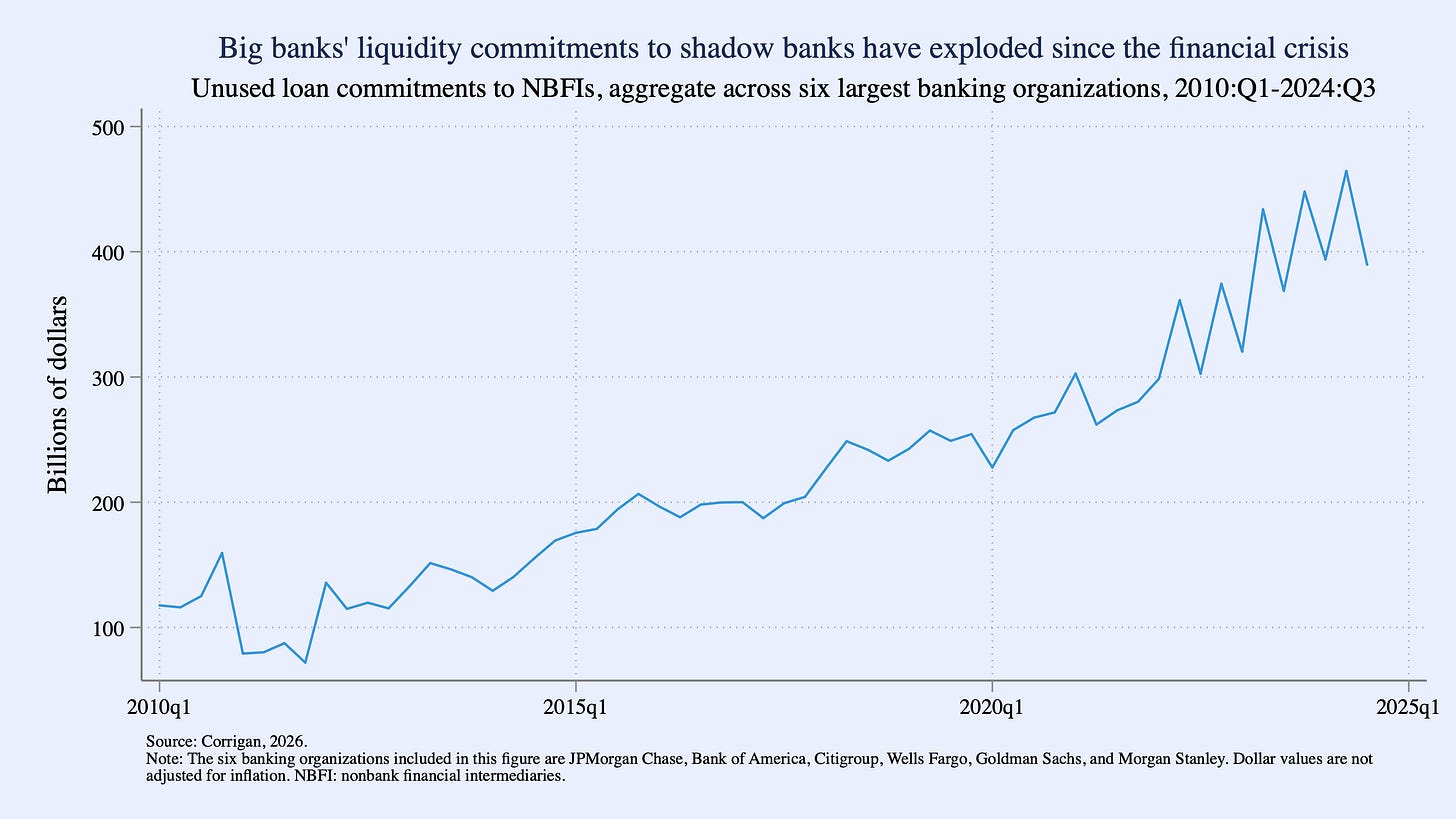

Recent research documents the extent of bank lending to nonbank financial intermediaries. Off-balance sheet contingent loan commitments ratchet up exposures.

Figure 1 shows that unused loan commitments to nonbank financial intermediaries (NBFIs) by the six largest banks have increased more than 4 times since 2010, with a 21 percent increase in the first three quarters of 2025 alone. Unused commitments to NBFIs stood at $531 billion as of the third quarter of 2025, a massive liquidity commitment that would provide a significant drag on the banking sector in a crisis.

Banking law and Federal Reserve require bank subsidiaries and affiliates to serve as a source of strength to the banking institution in a time of financial deterioration. In theory, the Federal Reserve can require affiliates and subsidiaries to use their financial resources to bail out the banks. But unused loan commitments to bank-sponsored funds flips this relationship on its head. If a financial crisis occurred tomorrow, banks would serve as a $500 billion plus source of strength to nonbank financial intermediaries and sponsored funds. Pre-arranged liquidity commitments to private funds effectively provide those funds with indirect access to the Federal Reserve as lender of last resort in a liquidity crunch. When liquidity tightens, private funds would draw on their bank credit lines, and banks would in turn access Federal Reserve liquidity facilities. Banks serve as conduits to extend the public safety net beyond insured depository institutions without corresponding prudential oversight of the ultimate beneficiaries.

Regulatory Arbitrage

The same lending and investment activity faces different regulatory treatment depending on where it occurs. Loans originated and held by banks are subject to capital requirements, supervisory examination, and lending limits. Loans originated by banks but held by affiliated private funds face none of these constraints. This disparity creates incentives to structure transactions in ways that minimize regulatory costs rather than optimize credit allocation.

Procyclical Amplification

Data on income impacts from bank equity investments shows high volatility and strong procyclicality—large gains during boom periods and significant losses during downturns. This pattern amplifies rather than dampens business cycle fluctuations, contrary to the diversification benefits sometimes claimed for these activities.

The Shadow Venture’s Prudential Risks Warrant Consideration of Policy Reforms

There are three tiers of potential regulatory response, which can be pursued independently or in combination. Option 1, enhanced mandatory disclosures, could provide more data that would be useful in answering the question of additional regulatory measures are warranted. All three proposals in combination would extend the Volcker Rule’s covered fund prohibitions to real estate, credit, and securitization funds. Because it would restrict principal investing by banks, but not customer-facing intermediation as agent, the proposal would be in intermediate step and not full return to Glass-Steagall’s structural separation of commercial and customer-faced investment banking.

Option 1: Enhanced Disclosure Requirements

Require banking organizations to provide detailed, disaggregated public disclosures of their equity investments in and liquidity commitments to nonbank vehicles, including transaction-level data for large investments. Researchers have raised concerns with the opacity of private credit. The relationships that constitute the shadow venture are just as opaque. Current reporting by public banking organizations aggregates exposures in ways that obscure the nature and concentration of risks. Disclosures should also include narrative disclosures tracking the risk factor and management discussion and analysis sections of public disclosures. Enhanced disclosures, especially at the consolidated bank holding company level, where monitoring and securities litigation by public investors can bite, would facilitate public market discipline, constraining moral hazard problem. Disclosures would also provide more information with which to assess supervision and policy responses. Regulatory guidance already encourages public disclosure of equity investment activities by banking organizations “given the important role that market discipline plays in controlling risks,” but banking organizations appear to make only the minimal disclosures required for off-balance sheet exposures in the footnotes to financial statement.

Option 2: Restrictions on Liquidity Commitments to Affiliated Funds

Treat large unfunded credit commitments from banks to funds and “financial” companies as unsafe and unsound practices. This would require banks to choose between equity investment and liquidity provision—they could not do both for the same vehicle. Regulation under the liquidity coverage ratio may assuage some concerns about the safety and soundness risks to banks of these lines of credit, but this depends crucially on how the lines are structured and whether the rules can be arbitraged (the coverage ratio for general credit is much lower than for liquidity management or general credit). Moreover, during a systemic shock to private capital, when banking organizations must sell hundreds of billions of dollars in high-quality liquid assets to support private capital, it is unclear whether sufficient buyers would exist to prevent firesale pricing.

The Volcker Rules Super 23A and Super 23B provisions are designed to obtain a similar result for bank-sponsored or owned private equity and hedge funds and other “covered funds.” But the credit and real estate funds in the shadow venture are exempted from the Volcker Rule’s covered funds rule. A more robust version of Option 2 would extend the Super 23A and 23B restrictions to any fund that meets the definition of “investment company.”

Option 3: Narrowing Volcker Rule Exemptions

Amend the Volcker Rule to eliminate or narrow the exemptions that currently permit bank investments in credit funds, real estate funds, and securitization vehicles. This would bring these activities inside the prudential perimeter, subjecting them to capital requirements and supervisory oversight.

As noted above, the Volcker Rule prohibits banks from sponsoring or holding ownership interests in most private equity and hedge funds. But the shadow venture exploits exemptions from the Volcker Rule’s covered fund prohibitions for real estate, credit, and certain other funds. Option 3 would eliminate the exemptions from the Volcker Rule’s covered fund provisions for credit, real estate, and securitization funds.

Conclusion

New evidence shows that the banking sector and private funds are deeply integrating. This new “shadow venture” challenges the narrative of a clean separation between banks and shadow banks, with banks de-risking by pushing risk out to shadow banks. The story instead appears to be one of increasing partnership through equity ownership and liquidity commitments. Much remains unknown about the rise of the shadow venture and its financial costs and benefits. But if prudential regulation continues to treat banks and private funds as separate domains, it will miss the institutional forms that increasingly matter for prudential regulation and risk repeating the familiar cycles of displaced risk.

Once again the financial sector cannot be trusted to manage risk appropriately. They are effectively reaping the profits from high risk investments while putting the assumption of that risk on the globe. The only uncertainty is when the next crisis will occur.