Los Angeles Shows That the Private Sector Can Develop Affordable Housing

Survey data from Los Angeles also show that a majority of residents support new building in their neighborhoods

Across the United States, an increasing number of metropolitan areas are experiencing a housing shortage that has led to an affordability crisis. There is a concurrent growing awareness that the primary cause of the affordability crisis is political: regulatory barriers decrease the supply of housing, increasing the price of houses. Cities and states around the country have started to respond by reducing minimum lot sizes (Austin), permitting larger multifamily buildings (New Rochelle, NY), eliminating mandatory single-family zoning and parking minimums (Oregon), and increasing density around mass transit stops (Minneapolis and California).

Since December 16, 2022, Los Angeles has attempted to expand middle-class housing by reducing regulatory barriers to building housing for individuals earning up to 120% of local area median income. Its experience highlights three lessons that can inform housing policy: (1) straightforward changes to permitting rules increases housing supply; (2) increased supply faces immediate opposition; and (3) contrary to conventional wisdom, this opposition, while often fervent, is a minority viewpoint. Responses to a large annual survey of Angelinos, the Los Angeles Quality of Life Index (LAQLI), shows that a majority of Angelenos supports apartment construction on single-family streets, and specifically in their own neighborhoods.

Los Angeles’ Streamlines Permitting, Increasing Supply of Affordable Housing

As a mayoral candidate, Karen Bass campaigned on reducing homelessness and improving housing availability. Four days after becoming Mayor on December 12, 2022, Mayor Bass issued Executive Directive 1. ED 1 introduced two policy changes, ministerial approval and faster application review time for “100% affordable housing projects, or for Shelter”.1 This change overcame prior permitting barriers that which added large costs and uncertainty to apartment construction. Ministerial approval is especially meaningful for projects over 50 units because the Los Angeles Municipal Code otherwise requires discretionary review even for projects compliant with zoning. These changes reduced project approval time from 6-9 months to 45 days, according to the Mayor’s office.

ED 1 applies to projects with at least five units that are “100% affordable housing,” defined as a building where 80% of units go to households earning below 80% of the area median income — $121,200 for a family of four in Los Angeles—and 20% of units for households earning $127,900. Affordable housing also caps rents for renters below 100% of area median income.

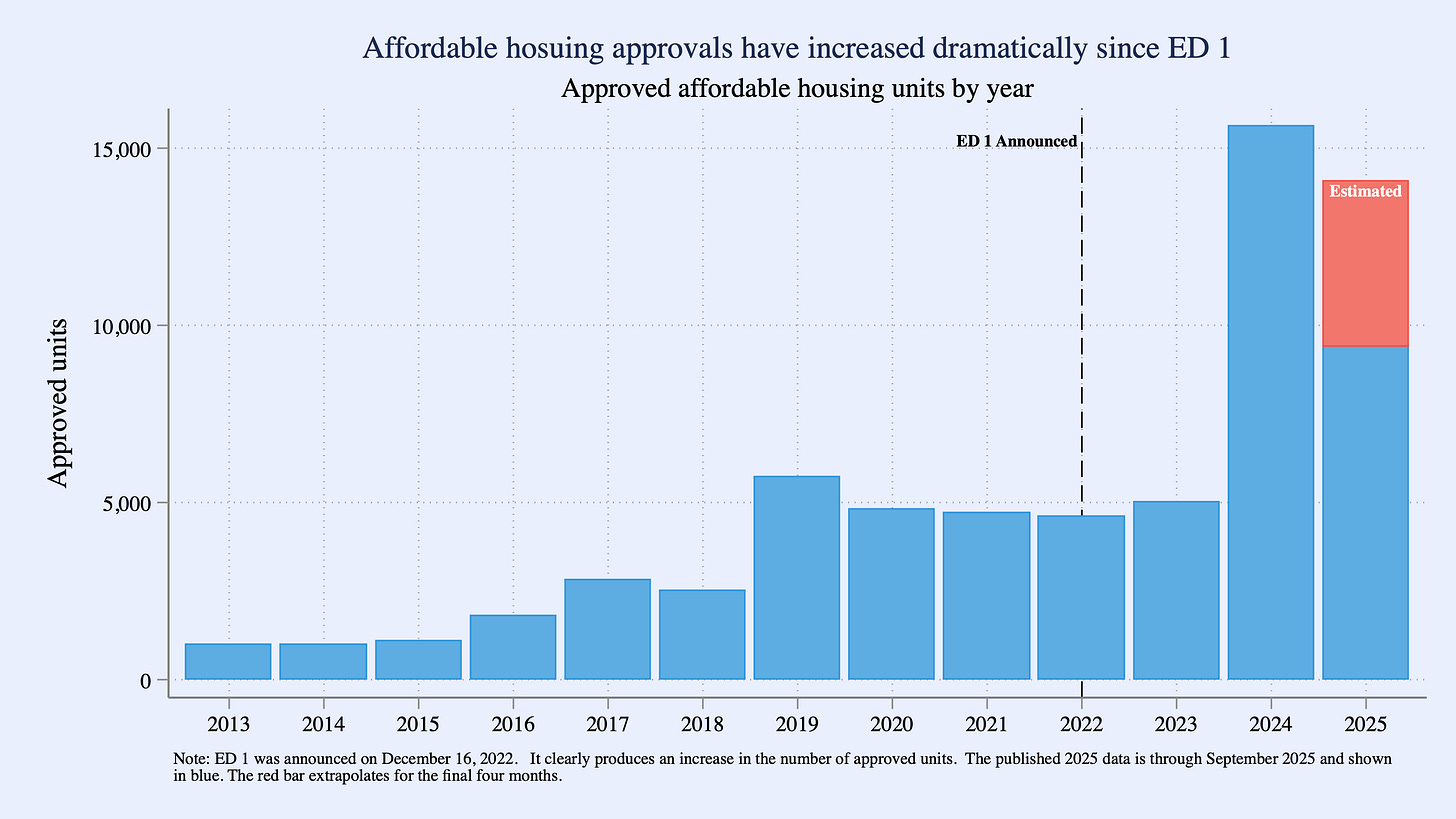

ED 1 unleashed a bonanza of housing applications. In 2023, applications for 13,770 affordable units were filed with the city’s planning department, more than the three prior years combined. As of September 16, the city’s planning department has received applications for 484 projects proposing 39,344 units, of which 394 and 29,910 respectively have received approval.2 By contrast, in 2022 only 4,600 affordable housing units were approved, and during the decade from 2013 to 2022 only 29,900 were.

Figure 1 combines data from the City Planning department on affordable housing approvals from 2013-2022 with the ED 1 resource portal’s data on affordable housing projects. The ED 1 stimulus is clear, with a lag.

Figure 1

Opposition to ED 1

ED 1 faced immediate opposition, leading to two notable curtailments restricting the number of lots available for ED 1 development. On June 12, 2023, ED 1 was amended so that “in no instance shall the project be located in a single family or more restrictive zone”, which is 74% of land in Los Angeles. On July 1, 2024, ED 1 was revised a third time, resulting in the version of record at the time of writing, seven pages long versus the original’s three.3 Sites in a very high fire hazard severity zone, on a hillside, replacing a historic building, in a historic preservation overlay zone, and that are zoned only up to are no longer available for ED 1 development. The change also restricts the number of density bonuses and waivers available.

At the April 17, 2024 UCLA Luskin Summit, an audience member asked Mayor Bass to explain the dilution of ED 1. “As a politician,” she explained, “you have to listen to your constituents. We were getting a lot of pushback against ED 1 for leading to housing where it was not expected.”

A Silent Majority of Angelenos Supports ED 1

While opposition to ED 1 was undoubtedly true, representative survey data shows that a strong majority of Angelenos support new apartment construction, even in their neighborhood.

The Los Angeles Quality of Life Index provides those data. Approximately 1,500 adult respondents are reached via random telephone dialing and online probability sampling. In 2023, respondents were presented with a question about their support for the location of new multifamily housing.4

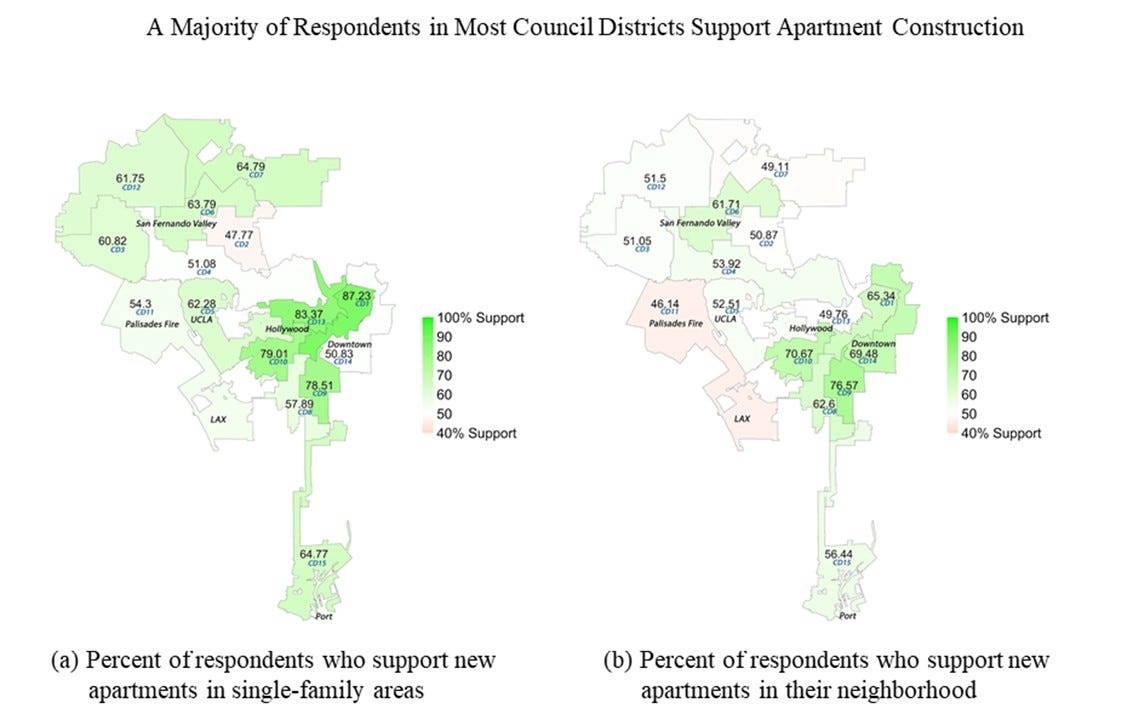

Figure 2 shows these results by City Council district. The left subfigure shows the percent of respondents who support new apartment buildings in Los Angeles, on streets zoned for single-family housing. The results clearly show that a majority of Angelenos in every district except one support new apartment construction on streets zoned for single-family homes. But support for building may depend on where the building takes place. The right subfigure shows the percent of respondents who support new apartment buildings in their neighborhood. Support for housing in one’s neighborhood is less widespread than on single family streets, but it still receives majority support in 12 of 15 districts.

Figure 2

Overall, 63.51% of residents support apartments “in streets that primarily have single-family houses”, and 58.83% support apartments in their own neighborhoods. This agreement is not driven by the preponderance of renters in Los Angeles, 60% of residents according to the Los Angeles Housing Department and 45.25% of respondents in the 2023 LAQLI. 58.83% of homeowners support new apartments in single-family areas and 49.40% support them in their neighborhood; the percentages are 64.8 and 64.6 for renters. There is overwhelming support across Los Angeles for more apartments in Los Angeles.

Policy Lessons

The private market can generate middle-class housing. Los Angeles provides no public monies to subsidize ED 1 projects. For qualified projects, ED 1 simply reduces bureaucracy and increases density. It also does not require union labor, lowering construction costs. With these tweaks, Los Angeles reoriented itself from saying no to housing by default to saying yes. The surge of applications from for-profit developers to construct income-restricted units, without government funding, gives lie to the notion that the market can only build luxury housing. The market only builds luxury housing because the jungle of regulations and reviews that are currently required creates costs that only luxury projects can overcome. While the term “affordable” evokes low-income housing, ED 1 is actually a middle-class housing program.

Policymakers must also better understand selection bias in public opposition, and opportunities to engage silent majorities. In the case of ED 1, constituents who have the time and ability to contact their elected officials were not representative of the broader constituency. People who make their voice heard are likely to be more educated, higher income, older, and homeowners, and the opinions of people with those characteristics often differ from those of people with different backgrounds. Inferring public opinion only from people who proactively make their voices heard leads to selection bias and eventually biased policy. High-quality surveys such as the Los Angeles Quality of Life Index are much more likely to be representative of the broader population.

Even when recognizing the aggregate benefits of new housing construction, local elected officials often oppose it on the belief that beneficiaries of it are not voters while those harmed by it are. The LAQLI results show this dynamic no longer holds, if it ever did. In Los Angeles, in a supermajority of districts, a majority of adults support new apartment construction in their neighborhood. Los Angeles City Council members can support new apartment construction with the protection of their public’s opinion.

Ministerial approval, also known as by-right approval, means no discretionary review of projects.

Some projects filed before December 16, 2022 were subsequently deemed ED 1 eligible. These numbers and all subsequent analysis exclude them.

The second revision moved the authority of ED 1 from the Mayor’s declaration of a housing emergency to the City Council’s recently passed revision to the Los Angeles Municipal Code defining such an emergency.

Specifically, question 27 asks:

Next, I am going to mention some locations where new apartment buildings could be built to make housing more available. For each one, please tell me if you would support or oppose new apartments being built there.

Locations were “your neighborhood”, “streets that primarily have single-family houses”, and “streets that primarily have retail stores, office buildings and other commercial uses”. Responses range from 1 for strongly support to 4 for strongly oppose, in addition to 5 for do not know. To turn the Likert scale into public opinion data, anyone who answers that they somewhat or strongly support new apartment buildings is recoded as supporting housing, anyone who somewhere or strongly opposes is recoded as not, and those who do not know are dropped.