Delivering the Future: Why the Postal Service Needs a New Model

From Self-Financing to Public Investment in National Infrastructure

The United States Postal Service needs a structural overhaul. For decades, Congress has asked this vast public system to operate as if it were a self-financed business, while asking it to do more than any private business would ever attempt. With more than 600,000 employees, 31,000 post offices, and six-day delivery to 169 million addresses, it is one of the largest and most important pieces of national infrastructure—a network that quite literally binds the country together. The self-funded model, created in the 1970s and sustained ever since, no longer matches the economic realities of how Americans communicate, trade, or live. Yet, its mission is more important than ever. The Postal Service is particularly critical for linking rural communities to the broader national economy, and any reforms to it must preserve its public service.

What most clearly distinguishes the Postal Service from any private carrier is its Universal Service Obligation (USO), or its legal and operational commitment to deliver mail and packages to every address, reliably and at uniform, affordable rates. This mandate applies as equally to mail destined for an office building in Manhattan as to a remote household in rural Montana, ensuring that geography, density, or profitability do not determine access to the national economy. No private carrier could or would operate under such terms. The USO is what transforms the Postal Service from a logistics company into a national infrastructure: it sustains service in markets that would otherwise be unprofitable, anchoring the Postal Service’s civic and economic value for communities that the private market has left behind.

A Growing Network but Shrinking Revenues: USPS is Doing More with Less

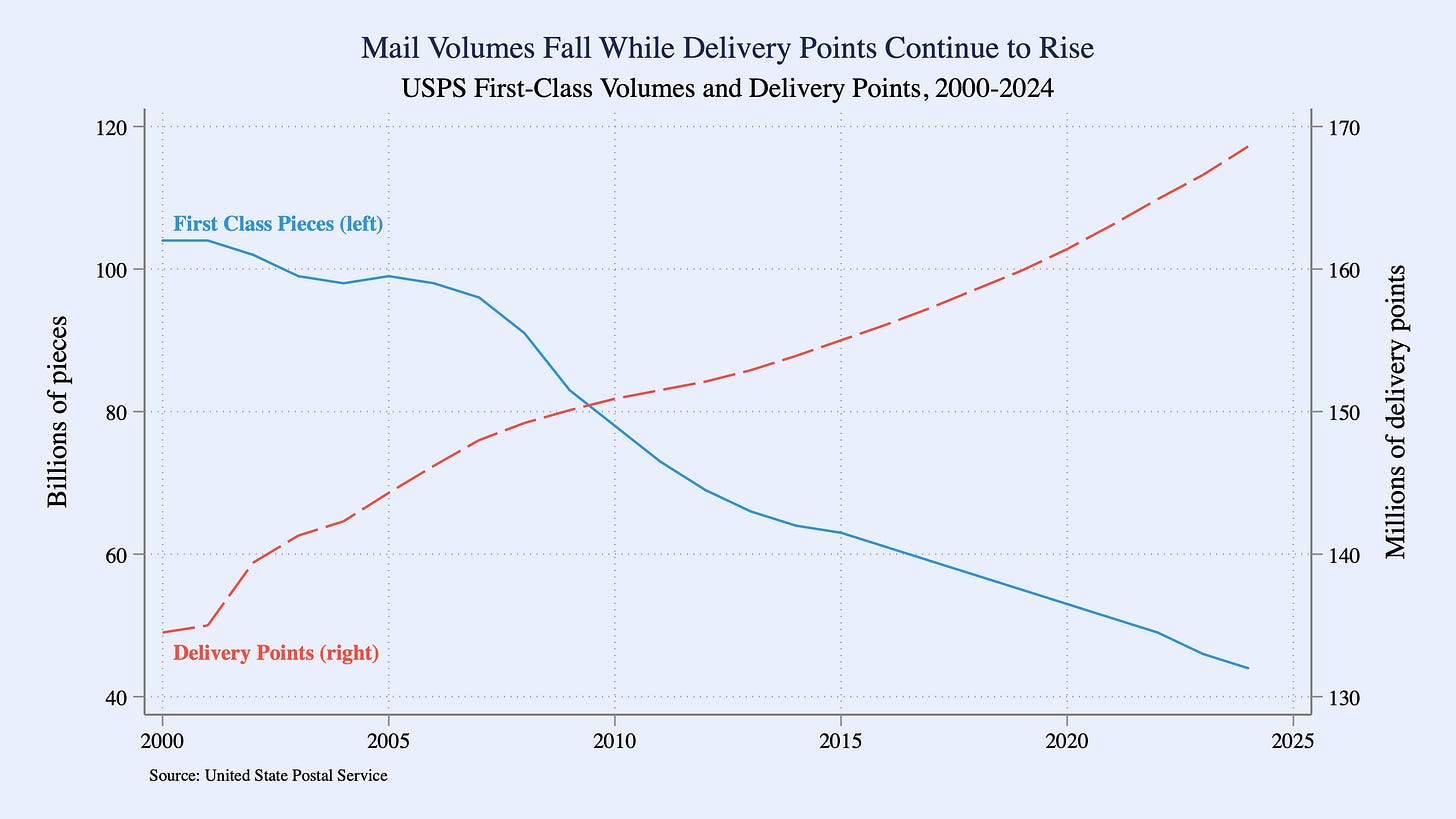

Over the last two decades, the Postal Service’s workload has grown while its core revenue base has eroded. Even while traditional mail volumes have fallen by more than half since 2000, the number of delivery points has increased by more than 30 million (Figure 1). Each year, the network must grow to meet its universal service obligation, reaching new addresses to serve a population that is larger, more dispersed, and more reliant on home delivery for essential goods than ever before.

Packages now account for much of the system’s growth, but package delivery has not replaced the revenue lost from letter mail. Competition in this sector is intense, and margins are thin, especially on the dense, profitable routes that its competitors dominate. Meanwhile, the Postal Service must deliver everywhere, including the less dense and rural places that its private market competitors do not serve, using infrastructure built for letters rather than parcels. The result is a system that must do more work, over a greater distance, with less revenue to sustain it. Despite these shifts, the institution still operates within a framework built for the last century, and it can’t meet the demands of our modern economy without real reform.

Postal Infrastructure: An Economic Imperative for National Connectivity

The Postal Service is more than a delivery network—it is one of the few institutions that still reaches every community in the United States, six-days per week. Its universal service obligation guarantees affordable delivery to more than 169 million addresses, regardless of geography or profitability. No private carrier duplicates its coverage; in fact, all rely on the Postal Service to complete deliveries in less-dense markets where the economics make service unprofitable.

For many rural areas, the Postal Service is a critical link to the broader economy. Nearly one in five Americans, or roughly 60 million people, live in rural communities, and roughly 90% of the land area served by the Postal Service is rural. Indeed, 30% of delivery points, one-third of delivery routes, and nearly 60% of post offices are located in rural areas. In these places, the Postal Service provides the most consistent point of federal presence, connecting communities that have seen banks, hospitals, and retail institutions disappear.

Post offices facilitate the delivery of prescription medicines, government checks, and ballots. They support small businesses that rely on affordable parcel delivery. And, they maintain a dependable channel for goods and correspondence where broadband and private logistics are limited. While population growth over the past two decades has concentrated in metropolitan and suburban areas, the physical postal network of more than 31,000 post offices has remained largely in place, reflecting the enduring obligation to maintain service in all parts of the country, not just where market demand is strongest.

The economics of that service are straightforward but consequential. Most delivery costs are route-based, driven by labor time, vehicle operation, and fixed schedules. The marginal cost of serving an additional address on an existing route is low, but dispersion increases the overall cost: rural routes cover more distance with fewer deliveries, raising the average cost per piece. These routes nevertheless sustain the last-mile network that underpins e-commerce and connects low-density regions to national markets. In this way, the Postal Service functions less as a stand-alone enterprise and more as shared infrastructure—a logistical platform that supports both private carriers and public needs. Recognizing that cost structure is essential to understanding how the system should be maintained and funded in the future.

A Funding Model Built for 1970 That No Longer Works

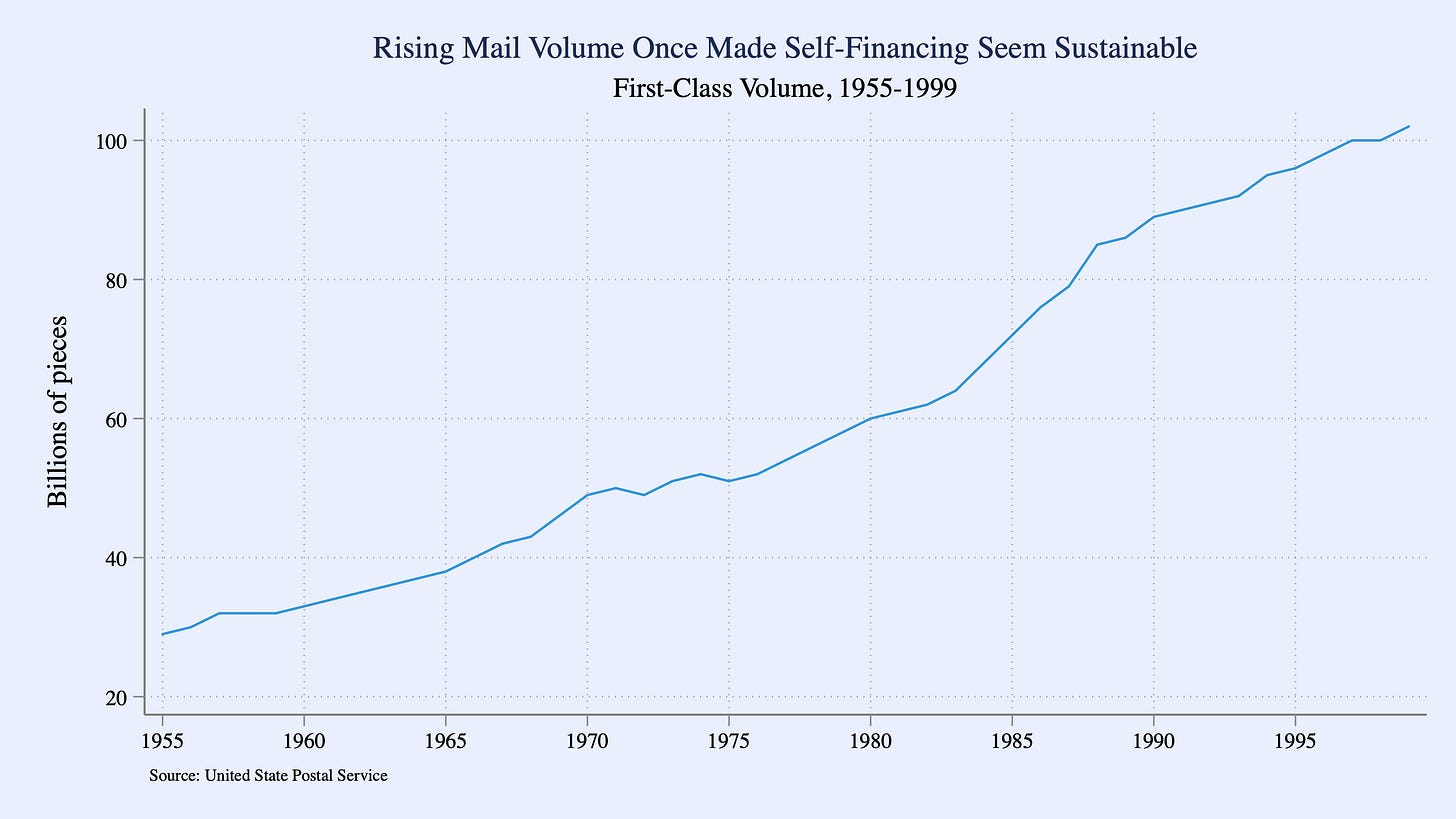

The modern Postal Service, and the funding model that continues to define it, was established by the 1970 Postal Reorganization Act (PRA). Before then, the Post Office Department functioned as a cabinet-level agency, financed through a mix of service revenues and congressional appropriations. The PRA transformed it into a self-funded, independent establishment of the federal government, overseen by a Board of Governors and monitored by the Postal Regulatory Commission. It also codified the postal monopoly—the exclusive right to deliver letter mail and access mailboxes—to preserve a stable source of revenue for universal service. At the time, this model appeared to be sound: the Postal Service was handling roughly 50 billion pieces and still growing rapidly (Figure 2). For the next three decades, mail volumes and revenues would rise in tandem, reinforcing beliefs that a self-financing structure could sustain the system indefinitely.

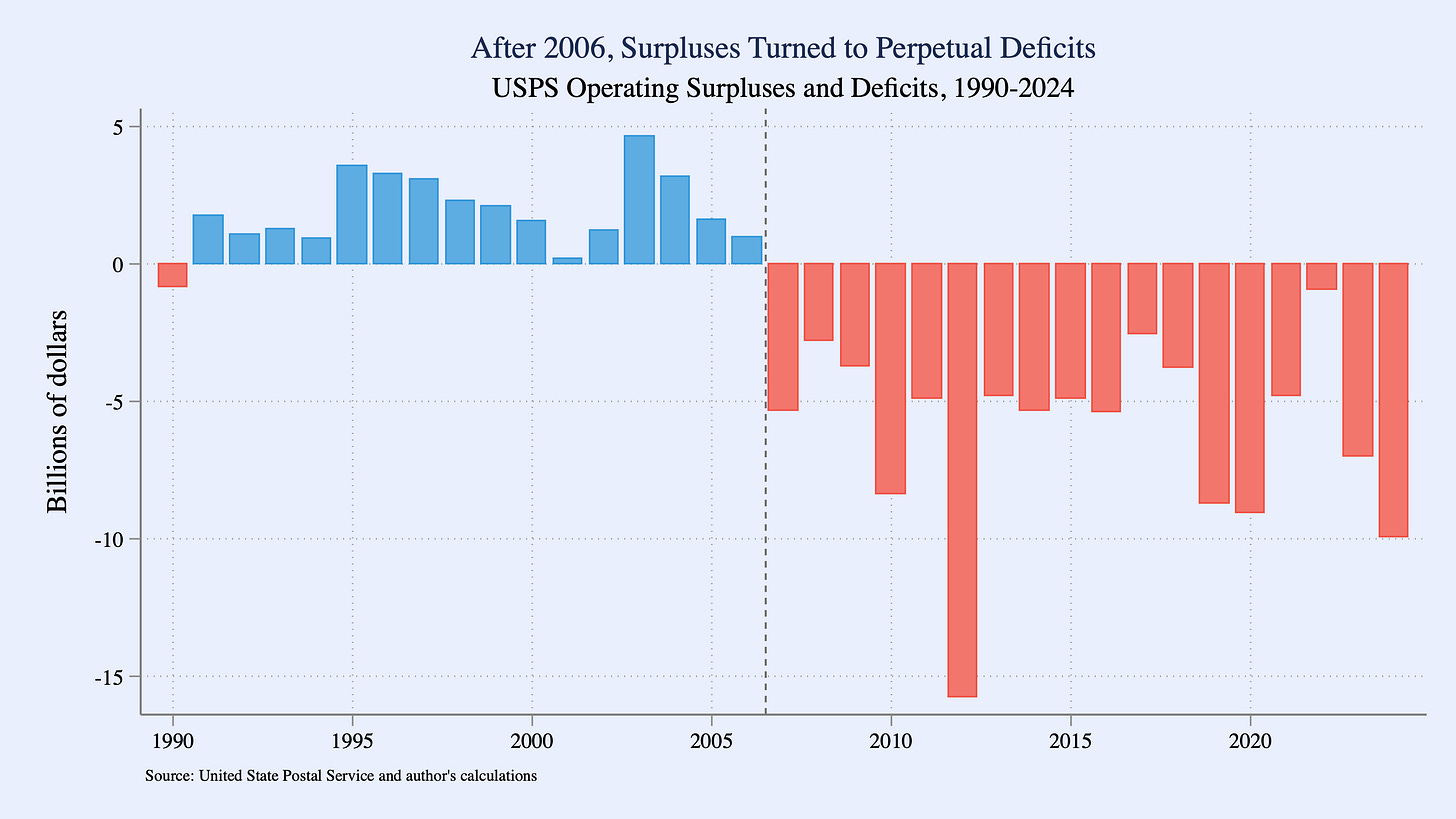

By the early 2000s, that confidence was deeply ingrained. The Postal Accountability and Enhancement Act (PAEA) of 2006 sought to modernize the Postal Service’s regulatory framework for a system that was stable and operating with near-constant, modest surpluses (Figure 3). The law introduced a new ratemaking process that limited price increases for market-dominant (monopoly-protected) mail products to the rate of inflation while giving the Postal Service greater flexibility to compete in the fast-growing parcel and shipping market.

Yet, the law’s most consequential provision was a requirement that the agency pre-fund retiree healthcare benefits. This mandate is unique in the federal government and rare in the private sector. Importantly in the context of the Postal Service’s financial solvency, this obligation added more than $5 billion per year to reported expenses.

Within a year of passage, however, the bottom fell out of the system. The Great Recession and the rapid shift to digital communication quickly eroded letter mail volumes, and with it, the very revenue that the Postal Service depended on. As shown in Figure 3, what had been a reliable surplus quickly reversed, and the combined effects of the prefunding obligation and collapsing demand turned a solvent agency into one that appeared to be permanently in deficit. In 2022, the Postal Service Reform Act (PSRA) finally removed the pre-funding requirement, relieving this budgetary pressure, but otherwise left the broader funding structure intact. Today, the Postal Service remains legally obligated to fulfill its public mission of universal service entirely through its own revenue—an arrangement that may have made sense in 1970, but one that no longer fits the scale or economics of its workload.

The Global Decline in Letter Mail: A Structural Shift Seen Worldwide

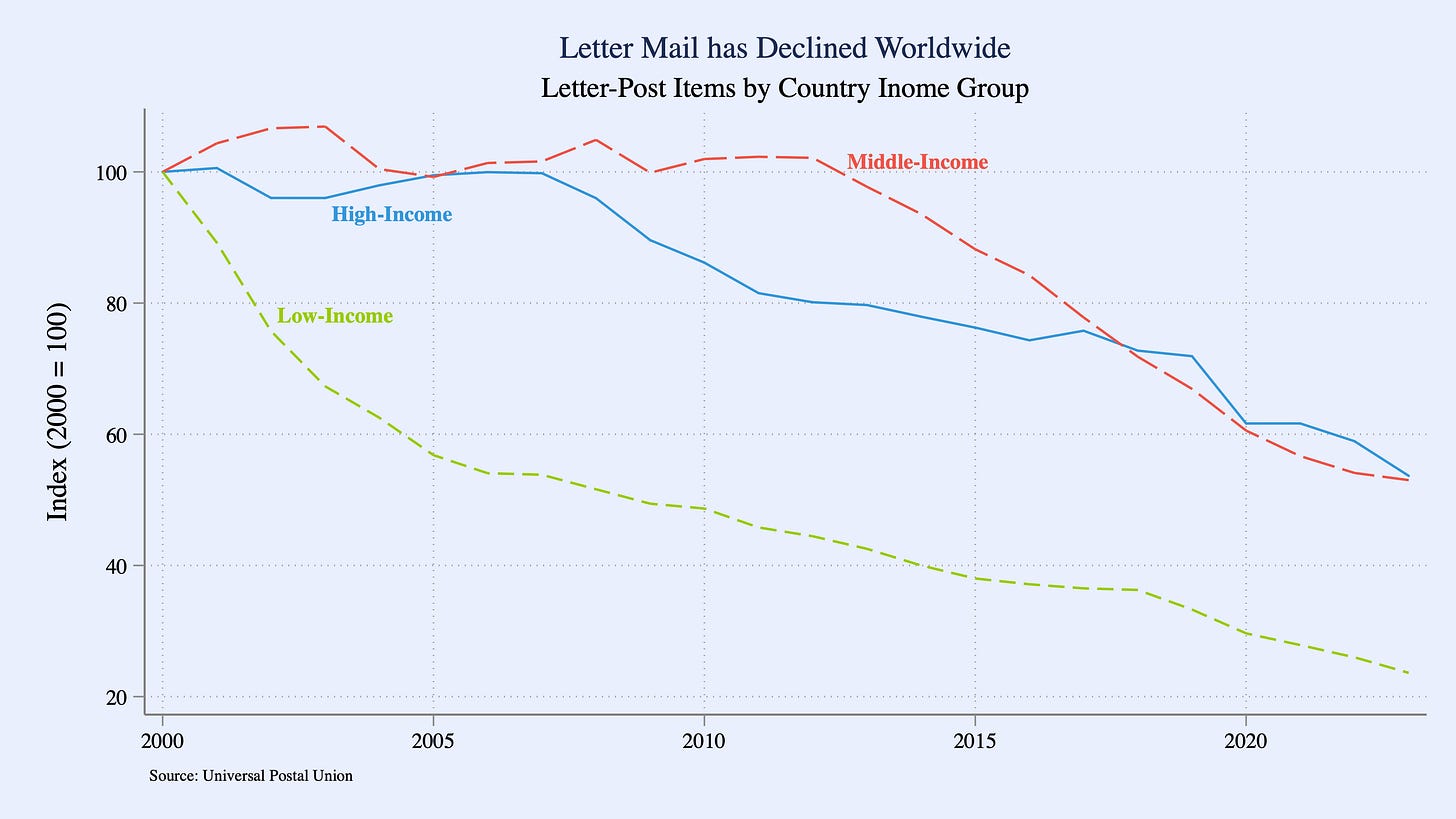

The American postal experience is hardly unique. Across the world, the digital substitution of paper has overturned the economics of national postal networks. Letter volumes have declined by roughly half, or more, in every income group of countries since 2000 (Figure 4). What distinguishes countries is not the direction of the trend, but their efforts to adapt in its wake.

The United Kingdom moved toward privatized Royal Mail in 2013, only to see the company struggle with labor unrest, cost pressures, and eroding service. Italy’s Poste Italiane has used profits from its banking and insurance arms to finance modernization, while France’s La Poste has relied on La Banque Postale to underwrite its network as it ventures into parcels, digital identity, and green logistics. Canada has begun scaling back—most recently ending most door-to-door delivery in an effort to contain mounting losses and adapt to declining letter mail. Denmark has gone even further, moving to end ordinary letter delivery altogether as digital mail replaces paper. These are different strategies for managing the same reality: mail revenues keep falling, and national posts everywhere are in financially precarious positions.

From Letters to Parcels: The New Postal Economics

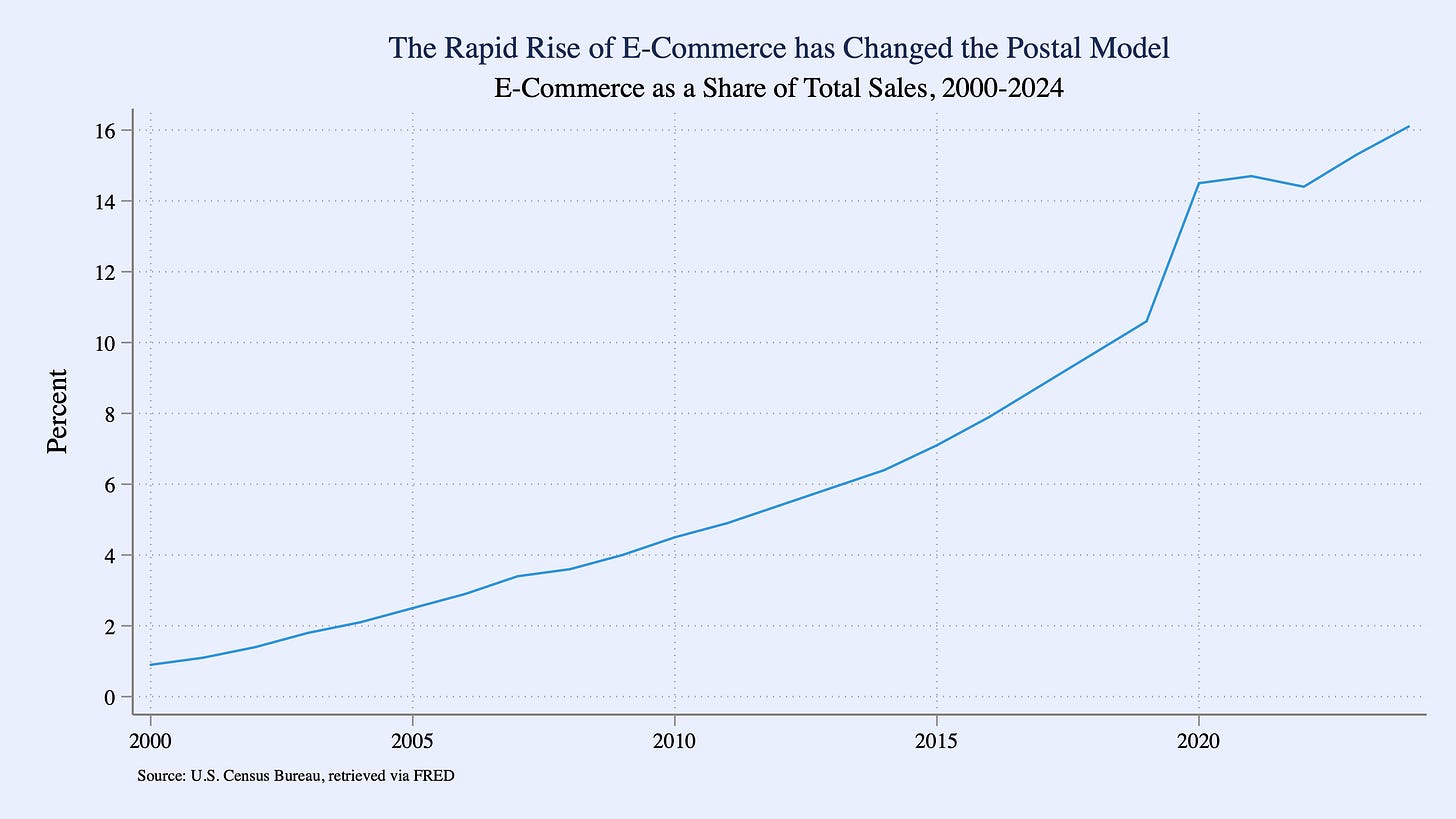

The future of the postal sector lies in parcel delivery. E-commerce has transformed postal operators around the world into delivery networks for moving goods rather than correspondence, and parcel traffic is growing worldwide. In the United States, e-commerce has grown from 1% of total retail spending in 2000 to 16% in 2024 (Figure 5). Packages now account for roughly half of the Postal Service’s revenue and more than 60% of total volume by weight.

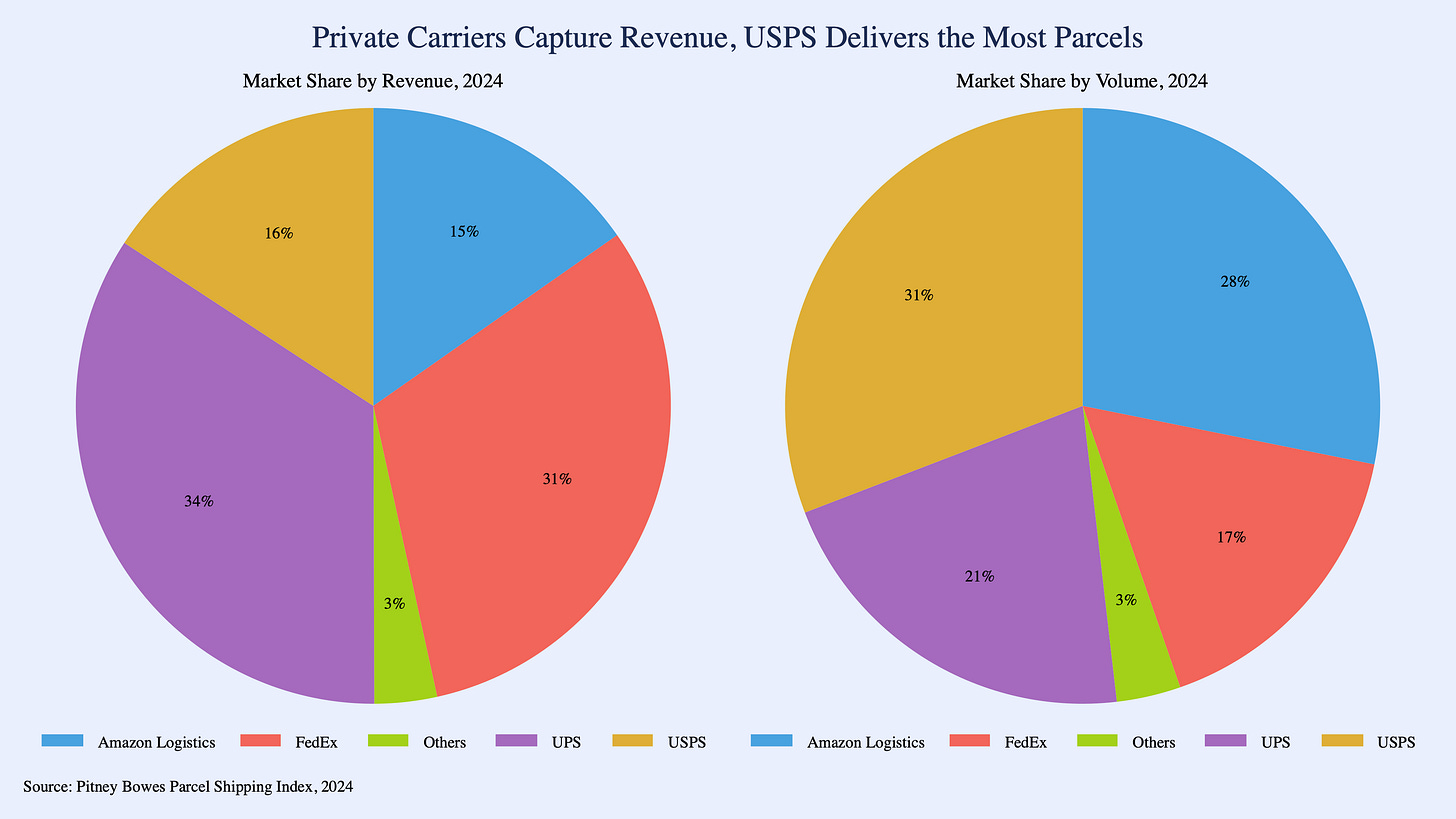

But, the economics of parcel delivery are far less forgiving than those of mail: competition is intense, margins are thin, and logistics costs are rising. FedEx, UPS, and Amazon Logistics are formidable rivals, capturing roughly 31%, 34%, and 15% of market revenue, respectively (Figure 6, panel A). These private carriers dominate high-density and commercial markets, leaving the Postal Service to cover the least profitable routes with infrastructure that was optimized for letters rather than parcels. In effect, the postal network sustains the last mile of the digital economy, bearing costs that private carriers and online retailers depend on but do not bear. Consistent with this imbalance, USPS moves about 31% of all U.S. parcels but only captures 16% of total parcel revenue (Figure 6, panel B).

From Self-Financing Back to Public Infrastructure: A New Model for the USPS

The United States operates the world’s largest and most capable postal network. USPS handles 44% of all mail volume globally and delivers to every address six-days per week over a geography that is larger than all of Western Europe combined. It is an active infrastructure that not only connects Americans to one another but also connects America to the world economy. For rural America in particular, the Postal Service remains a crucial point of continuity by linking communities that have lost banks, hospitals, and retail institutions to a national market. Where private carriers must optimize for density and profit, the Postal Service provides the connective tissue that ensures both the shared success of the parcel economy and equitable geographic access to it.

In 2021, the Postal Service introduced its ten-year strategic plan, Delivering for America (DFA). Framed as both a path to financial stability and a reinvestment strategy, the plan promises new facilities, vehicles, and technology upgrades. Yet its reinvestment is defined by the limits of the self-financing model—it seeks efficiency gains and balance-sheet improvement at the expense of the public mission. The plan’s savings are expected to come from network consolidation, revised transportation schedules, and slower delivery standards, alongside a greater emphasis on parcels and other “competitive” products.

The Postal Regulatory Commission (PRC) has raised persistent concerns about this approach, warning that the strategic plan will have “disproportionate impacts [that] will most greatly affect rural citizens and businesses who rely heavily on the Postal Service,” and that the plan “relies on overly optimistic and unsubstantiated financial projections for cost savings that are not likely to improve the financial health of the Postal Service.” In effect, Delivering for America proposes many of the same cost-cutting measures that a private carrier would adopt to improve margins: reducing service on costly, rural routes, and prioritizing balance sheet performance over public mission.

Some have argued that privatization could offer a path forward for the Postal Service. But, experience abroad and analysis in the United States suggests otherwise. Privatization would erode the universal service that distinguishes the network, not preserve it.

The only sustainable future for the Postal Service is on which Congress recognizes the Postal Service for what it already is: a national infrastructure rather than a self-contained business. The expectation that universal service must be self-financed must end. Public funds should instead support the fixed costs of delivering to every address, while enabling a modernization agenda that has been deferred for more than a decade.

This agenda should include electrifying one of the world’s largest civilian vehicle fleets, optimizing logistics for a parcel-dominant system, and re-establishing post offices as civic access points in communities where the federal government has few others. It should also cultivate the public-private partnerships that already define the U.S. postal economy, including collaborations with e-commerce retailers, logistics firms, and local governments that extend the reach of both market and state.

No private carrier can match the scale of the Postal Service, and no market mechanism can sustain it indefinitely. The choice, therefore, is not whether the United States will have a postal system, but what kind of system it will be: one that continues to optimize around a broken business model, or one that recognizes the postal network as a public good that is essential to economic and civic life.

Great post (no pun intended). One thought I had is that there should be a specific tax on online retailers for the Post Office. Today, online retailers get last-mile delivery at an absurd discount. The Post Office is subsidizing these businesses. Also, and this isn't thoroughly thought out, does it make sense that the urban/suburban "we" are subsidizing rural areas? I get that we city dwellers eat food produced by rural farmers, but farmers and the economy around them are not as significant as they used to be. I realize that this is heresy, but I feel like we need to have an honest discussion - especially since rural has way more political clout than their population justifies.

For some, stagecoaches were vital National Infrastructure. Until they were not.

The internet already provides connectivity to America's rural population. There is zero need for six day a week service to ANY postal address.

The only other benefit to daily delivery might be the rapid provision of medications. But that is surely a red herring. At a slight increase in costs, the commercial carriers can handle this.